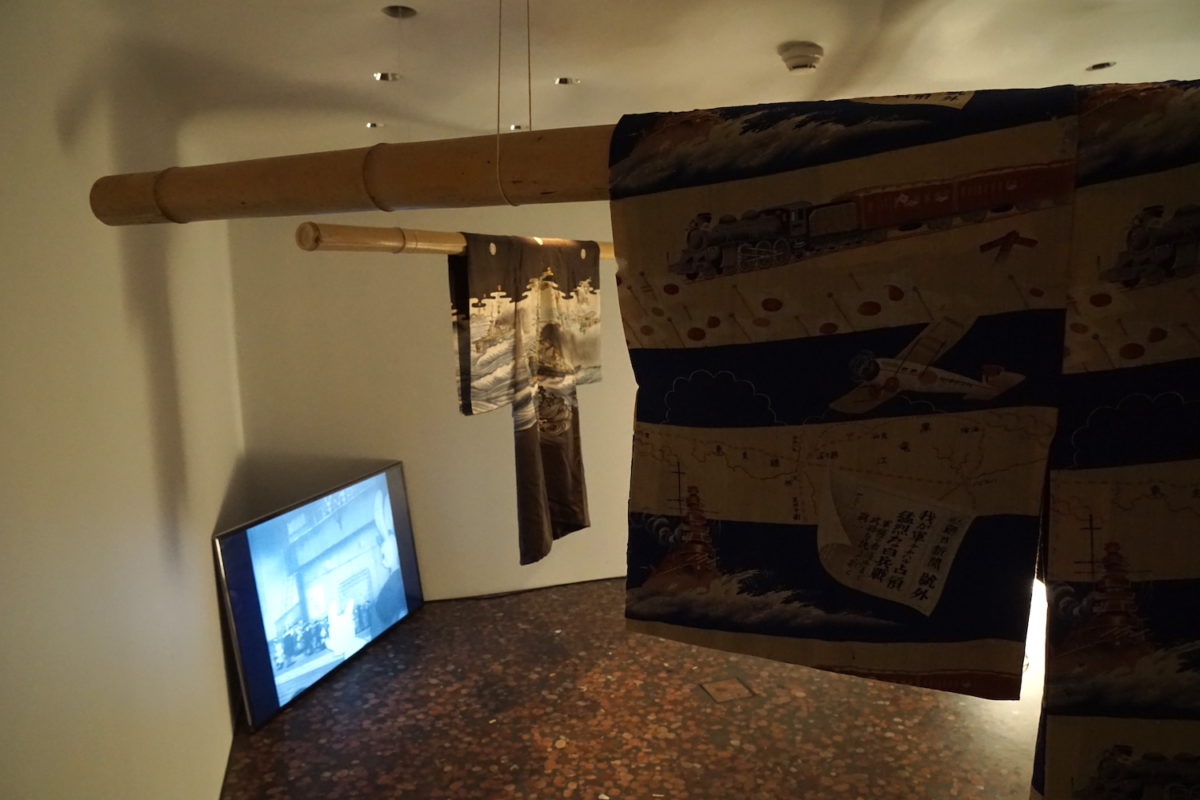

The exhibition Omoshirogara – Japan’s Path to Modernity explores the singular moment of Japanese modernization. Here we take a cue from illustrations and patterns on kimonos designed and worn during the turbulent period between 1900 and 1940. On the one hand, the kimonos show day-to-day life in a Japan pervaded by Western technology (with images of airplanes, iron bridges, skyscrapers and telegraph, for example). Yet they also propagandize the imperialist ambitions of the Empire of Japan, which – since its victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 – encountered the West as an equal partner, and sought to establish itself as a world power through territorial acquisitions in China, Korea, and in the wider Pacific region.

A careful look at these spectacular, rarely shown kimonos reveals how established Japanese patterns of perception and design were intertwined with elements of Western life (baseball, Mickey Mouse, the Berlin City Palace, the coronation of George VI). This interdependence is something altogether different from what is commonly called “Westernization.” The drama that plays out on these kimonos is that of the aesthetic incorporation of the West – on Japanese terms.

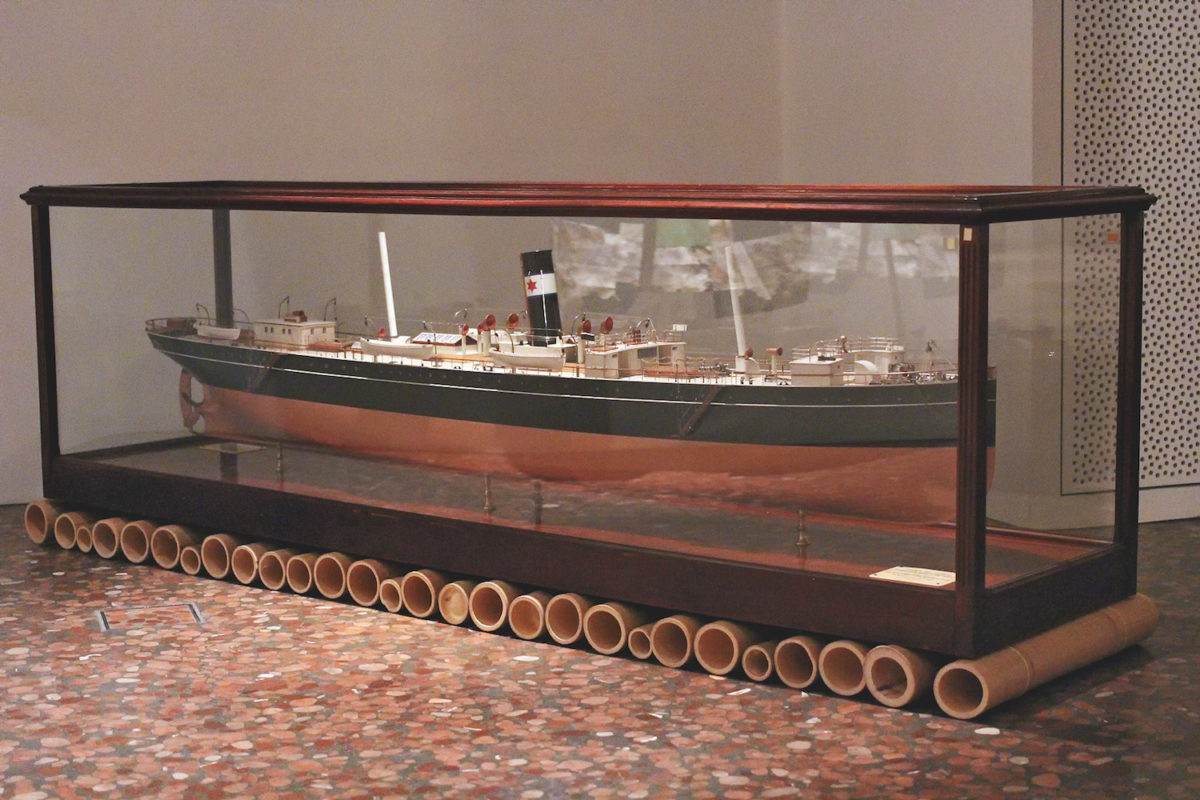

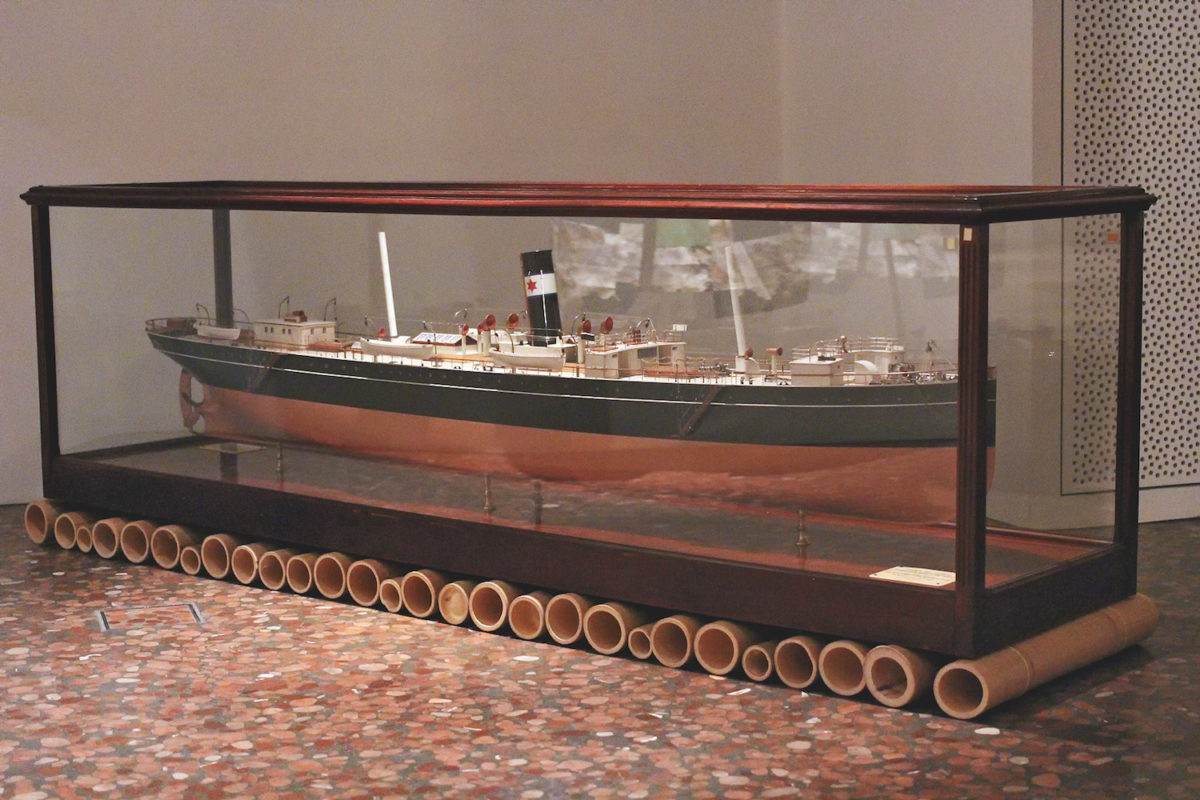

In addition to the kimonos we will also be showing the historical model for the Yamashiro-maru (mountain fortress), a 2500-ton passenger and cargo ship. Commissioned by the Japanese and built in England in 1884, the Yamashiro-maru can be seen as emblematic of the Meiji Restoration. Over the course of its turbulent history, the Yamashiro-maru transported thousands of Japanese migrants to Hawaii, was coverted to a torpedo mothership during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), facilitated travels between Korea, Taiwan and Vladivostok, and finally served as a hospital ship in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05).

The Yamashiro-maru is the subject of a research project led by Prof. Dr. Martin Dusinberre (Chair of Global History at the University of Zurich).

The exhibition Omoshirogara—Japan’s Path to Modernity is developed in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Hans B. Thomsen (Chair of East Asian Art History at the University of Zurich) and Sara Gianera, M.A., Leonie Thalmann, B.A., Fabienne Pfister, B.A., Anna-Barbara Neumann, B.A., Anjuli Ramdenee, B.A. and Alina Martimyanova, M.A..

The Kimonos are being kindly provided by Galerie Ruf Beckenried (Switzerland).

#1

And when did modern Japan begin?

Could it have been the mid-19th century, when US Commodore Matthew C. Perry and his fleet of armed vessels reached the bay of Edo (present-day Tokyo), to force trade relations with the island nation – a country that had all but sealed itself off from the West for centuries?

The Japanese knew exactly what was in store for them. Western gunboat diplomacy, including the Opium Wars in China, followed one and the same pattern: the breakup or dissolution of national sovereignty followed by a second step – dictating the terms of trade. To avoid this fate, Japanese elites decided to rapidly transform Japan into a fortified industrial country that could compete with the West. Though the tour de force became known as the “Meiji Restoration” (after the Emperor at that time), it was more of a revolution that affected all aspects of Japanese life from 1868 forward.

The shogunate was replaced by a constitutional monarchy, whereby significant parts of the new constitution matched that of the Prussian Reich (including the same, fatal clause that shielded the military budget from parliamentary scrutiny). The new dress code followed Western models as well; Emperor Meiji dismissed the traditional clothing of Chinese origin as “effeminate.” The kimono, now worn or shown by men mostly in private, gradually took on a new role: as a reflexive guarantor of Japanese values. These values could be expressed both in the kimono’s ceremonial function (also for children) and in its media function as civilian propaganda. Women, in their role as guardian of tradition under patriarchal conditions, continued to wear the kimono in public as well, although exceptions such as the mogā (derived from “modern girl”) proved the rule.

Among the cornerstones of the island nation’s modernization were its powerful navy and merchant fleet. One of the first Japanese steamers was the Newcastle-made “Yamashiro-maru” (1884), the original model of which is on view in the Johann Jacobs Museum. The example of this ship, which both transported Japanese migrant workers to Hawaii and served as a torpedo mothership during the Russo-Japanese War (1904/05), sheds valuable light on the complex drama of Japanese modernization.

Processes of modernization and industrialization increased the Japanese need for raw materials and foreign exchange. Very much in the style of European imperialism, the new regional power began to secure economic spheres of influence in East Asia. In the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Japan conquered present-day Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands, which continue to haunt the news as an area of conflict. Japan saw another victory with the Russo-Japanese War (1904/5), when it captured the southern tip of Manchuria and the Korean peninsula. The Japanese triumph over the Russians represented a beacon for the Japanese; it was the first time a non-Western power had successfully defeated a Western army since the Middle Ages.

Japan profited from the First World War in its new role as an exporter of ammunition and other materials. It sat on the side of the victors at the Versailles Peace Conference, next to the United States, Great Britain, France and Italy, the countries responsible for creating the postwar order. Tokyo, which was rebuilt after a devastating earthquake in 1923, developed into a dynamic metropolis, with a population that grew from 3.7 million (1920) to 7.4 million (1940) (compared to 6.9 million in New York [1930] and 4.9 million in London [1930]).

Japan annexed resource-rich Manchuria in the 1930s, and used it to launch a war against China in 1937. Imperialist visions of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” under Japanese leadership continued in the context of the Second World War, leading to Pearl Harbor and later, Hiroshima.

Looking at the kimonos with this transformative, groundbreaking era in mind, a contemporary viewer will note a parade of themes including modern technology, military strength, colonial expansion and highly individual, though selfless heroism. Adding to this is the aesthetics of the modern city with its skyscrapers, bridges, cars and railways and the visual language of cinema, fashion and advertising. All of these rather disparate elements are conceptually and technically interwoven with each other in a virtuosic way; the forms of omoshirogara are entirely consistent. The key to their success lies in the same capacity for abstraction that has fascinated the West since its first encounters with Japanese culture.

#2

The Kimonos

Nagajuban (for men) with a map of Manchukuo, silk (late 1930s)

Lines meander across surfaces, drawing a picture of Japan’s territorial expansion. The three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning in the upper part are marked with gray and beige, while the Korean peninsula (colonized 1910) is kept a reddish brown. The discreet coloring traces back to the “48 brown and 100 gray tones” that Sen no Rikyū (1522-91) once propagated in terms of focusing on the essentials for the Japanese tea ceremony. The lines in turn show the rail network for the Japanese railroad company Mantetsu.

Lines meander across surfaces, drawing a picture of Japan’s territorial expansion. The three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning in the upper part are marked with gray and beige, while the Korean peninsula (colonized 1910) is kept a reddish brown. The discreet coloring traces back to the “48 brown and 100 gray tones” that Sen no Rikyū (1522-91) once propagated in terms of focusing on the essentials for the Japanese tea ceremony. The lines in turn show the rail network for the Japanese railroad company Mantetsu.

Mantetsu was a driving engine of Japan’s modernization. Supplies of coal, steel and soybeans clattered into resource-poor Japan along its railway lines, which were rapidly installed with the help of tens of thousands of Chinese coolies. Japanese migrant workers traveled to Manchukuo on the way back. The workers hired themselves out as farm laborers, mine removers or in brothels (tens of thousands of daughters of impoverished farmers and fishermen were bought by organized pimps rings and forced into prostitution, especially during the the Meiji era. They were known as karayuki-san or “Woman who went over there”).

Newspaper clippings in the middle of the map report of a Chinese bomb attack on the Mantetsu. This “Mukden Incident” on September 18, 1931 marked a critical turning point in Japan’s colonial strategy. If the expansion was economically motivated at first, the attack served as a pretext for a military invasion, leading to the creation of “Manchukuo,” a puppet state governed by the last Chinese emperor Henri Pu Yi. After 1945, it came to light that the incident was staged and perpetrated by officers of the Japanese Kwantung Army.

Haregi (for children), silk (1940/41)

The design of this kimono captures the drama and sense of awe that would have been felt when watching a squadron of bombers fly across the sky as they carry out a mission.

The design of this kimono captures the drama and sense of awe that would have been felt when watching a squadron of bombers fly across the sky as they carry out a mission.

The aircraft represented here is most likely the Mitsubishi G4M, a Type 1 aircraft that was the main two-engine, land-based bomber used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service in World War II. The Japanese Navy pilots gave it the nickname of Hamaki (“Cigar”) due to its cylindrical shape; Allied troops called it “Betty”. The G4M first flew in 1939 and was designed for long range, high-speed flights. Early models went action in 1940 and served in battles in Northern China. The plane was in full production by 1941 and played a prominent role in attacks on Allied shipping once World War II began. Nearly 2.500 units were produced between 1941 and 1944.

It is possible that this garment was used for a boy’s first shrine visit or other important ritual. It is made of high-quality textile and carries imagery that would have been auspicious meaning for a boy child, with the airplanes expressing a sense of power, modernity, commitment and determination, all desirable qualities for male children. The textile would have made an equally dramatic presentation as a man’s nagajuban.

Jacqueline M. Atkins for Galerie Ruf Beckenried

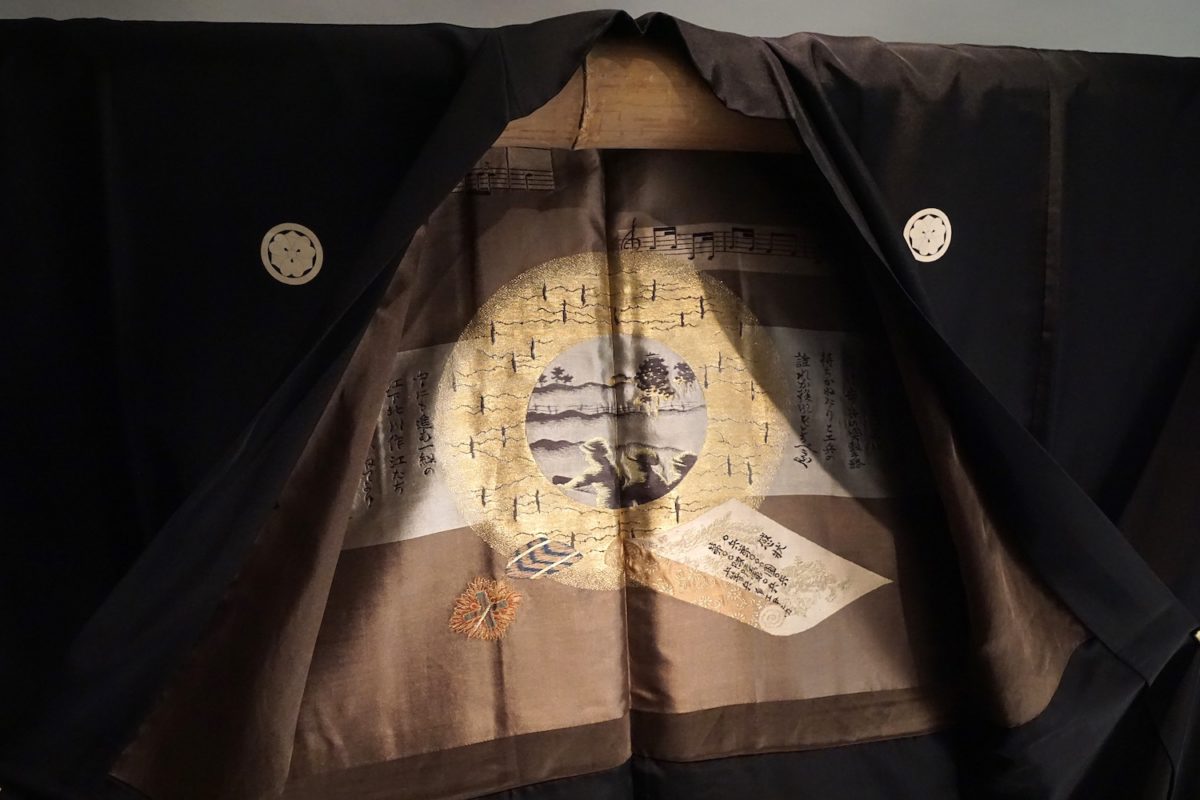

Haori (for men), silk (1932)

This kimono shows three soldiers who committed suicide by blowing themselves up with a bomb in 1932 (the “Three Brave Exploding Soldiers” Bakudan sanyūshi 爆弾 三勇士, also known as “The Three Brave Human Bullets” Nikudan sanyūshi 肉弾三勇士). The medal and certificate on this textile symbolize the honors that were posthumously awarded the three soldiers. The image depicts the three, holding the long bomb and preparing themselves for their fatal task; they are looking at the fence in front of them and the city of Shanghai in the distance.

During the Second Sino-Japanese war, the

three soldiers Eshita Takeji 江下武二,

Kitagawa Susumu 北川丞, and Sakue Inosuke

作江伊之助 took a key part in the siege of

Shanghai. On February 22, 1932, the

Japanese troops were held back, unable to

press through the seemingly impenetrable

fortifications of the defending Chinese. At

which point the three soldiers carried a long

tubular bomb through the non-man’s land

and up to the enemy fortifications. The bomb then exploded, killing the soldiers and opening a hole in the Chinese defensive line. This apparently proved to be the turning point of the battle for Shanghai.

The Japanese government announced the death of the three and trumpeted their explosive heroism to the nation. But interestingly, publicly owned media did most of the actual work of publicizing the death of the three soldiers. First of all, two rival newspaper groups competed with each other in making this a major media event. The three soldiers were even given different names by the competing newspapers. The Osaka Mainichi Shinbun and the Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun called them the “Three Brave Exploding Soldiers” Bakudan sanyūshi 爆弾三勇士, while the Asahi newspapers from Osaka and Tokyo called them the “The Three Brave Human Bullets” Nikudan sanyūshi 肉弾三勇士. Both of the newspaper groups commissioned songs on the topic and both gave prizes to their respective winners. The songs were enormously popular until the end of the war. They can be listened to here:

The Song of the Three Brave Exploding Soldiers

Bakudan sanyūshi no uta 爆弾三勇士の歌

The Song of the Three Brave Human Bullets

Nikudan sanyūshi no uta 肉弾三勇士の歌.

The story of the three soldiers became a sensation in other media and within weeks, no fewer than five movies appeared in Japanese cinemas. Two appeared on March 3, another on March 6, another on March 10 and March 17. In addition to a multitude of books on the three soldiers, a number of other commercial goods appeared in stores:

the three soldiers now (posthumously) promoted their own candy, a hair conditioner, and a line of western-style clothing. And they of course also appeared on textile designs, as can be seen in the Ruf kimono. Their story and songs became a standard part of elementary school textbooks, at least until the end of the war. The theme also appeared in public places. An example is the bronze statue in a public park in Tokyo.

The story of the three soldiers became a sensation in other media and within weeks, no fewer than five movies appeared in Japanese cinemas. Two appeared on March 3, another on March 6, another on March 10 and March 17. In addition to a multitude of books on the three soldiers, a number of other commercial goods appeared in stores:

the three soldiers now (posthumously) promoted their own candy, a hair conditioner, and a line of western-style clothing. And they of course also appeared on textile designs, as can be seen in the Ruf kimono. Their story and songs became a standard part of elementary school textbooks, at least until the end of the war. The theme also appeared in public places. An example is the bronze statue in a public park in Tokyo.

The musical notes on the top of the

Ruf textile are from one of the two

famous songs that were made in the

days following their announced death in the newspapers. This particular version became the most famous and

was published and promoted by the Osaka Mainichi Newspaper in March of 1932. It was entitled “The Song of the Three Brave Exploding Soldiers” Bakudan sanyūshi no uta 爆弾三勇士の歌.

The song has ten verses, and the lyrics of the first four verses are written in the middle of the textile composition:

Verse One

廟行鎮の敵の陣

我の友隊すでに攻む

折から凍る如月の

二十二日の午前五時

Verse Two

命令下る正面に

開け歩兵の突撃路

待ちかねたりと工兵の

誰か後をとるべきや

Verse Three

中にも進む一組の

江下 北川 作江たち

凛たる心かねてより

思うことこそ一つなれ

Verse Four

我等が上に戴くは

天皇陛下の大御稜威

後に負うは国民の

意志に代われる重き任

The lyrics were written by the famous composer Tekkan Yosano 与謝野鉄幹 (1873- 1935), who was also a professor of music at the Keiō University. The music was a joint composition by the military musicians Ōnuma Satoru 大沼哲 (1889-1944) and Tsuji Junji 辻順治 (1882-1945).

To give an impression of the speed of reaction by the contemporary media, the competition for the best song to commemorate the three dead soldiers was announced by the two newspaper groups at the end of February 1932 and vinyl records of the two songs were already placed for sale in the record shops in April of the same year. The design on the Ruf textile should be seen in the contemporary contexts of this story – the story was everywhere and was actively supported in various media. It would have been seen, heard, and read everywhere. Viewers would have understood the design instantly and would perhaps have started humming the songs to themselves.

Prof. Dr. Hans Bjarne Thomsen

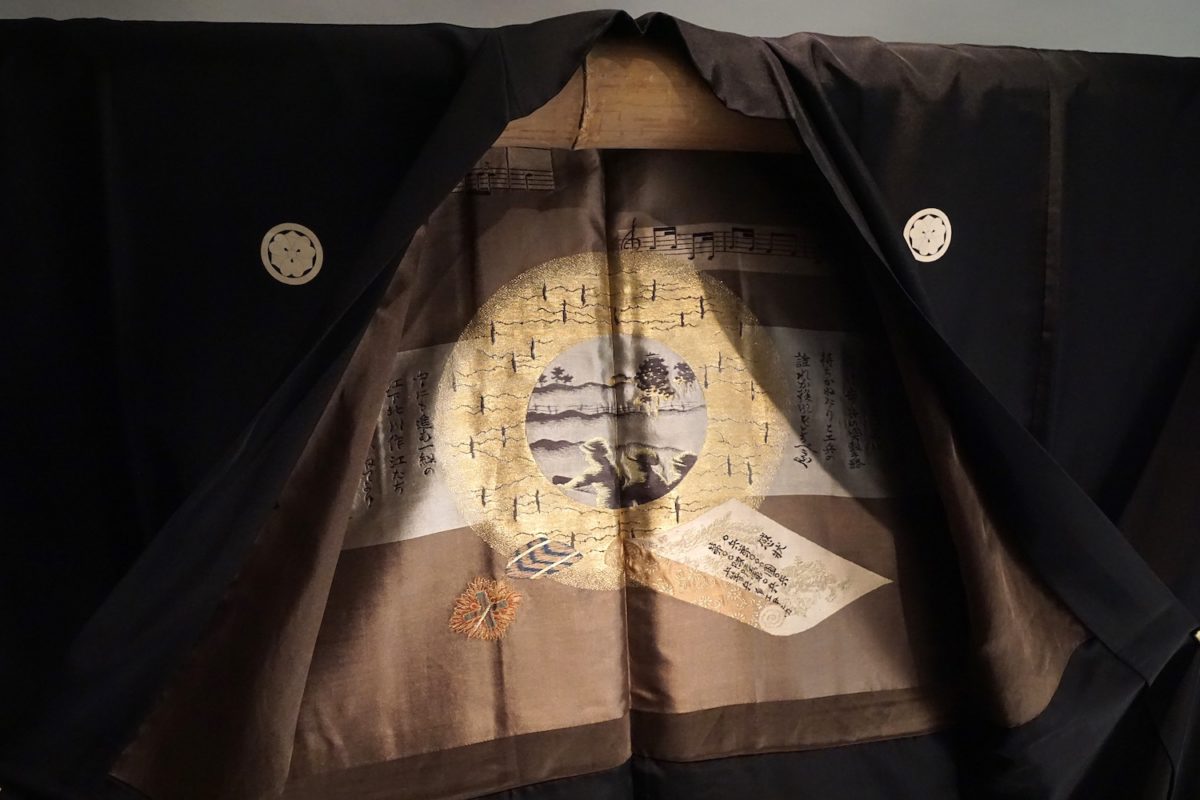

Kimono, silk (1904/05)

The calligraphy in the design is by the famous Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō 東郷平八郎 (1848-1934). The words are his command to his fleet at the climatic naval Battle of Tsushima of the Russo-Japanese War on May 27th, 1905. His actual words were: “This single battle will determine the glory or destruction of our imperial nation. Every person must give his utmost effort!” 「皇国興廃在比一戦各員一層奮励努力」.

The calligraphy in the design is by the famous Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō 東郷平八郎 (1848-1934). The words are his command to his fleet at the climatic naval Battle of Tsushima of the Russo-Japanese War on May 27th, 1905. His actual words were: “This single battle will determine the glory or destruction of our imperial nation. Every person must give his utmost effort!” 「皇国興廃在比一戦各員一層奮励努力」.

The composition seems at first view to be composed of two disconnected images, with a mountain landscape at top and a naval battle at the bottom. But the composition is connected and refers back to Tōgō’s very words: the image shown at the top depicts the Shinto Shrine at Ise, the most sacred site of the Shinto religion and a place closely associated with the Imperial family and nation. The message is clear: that the naval battle below is for the “glory or destruction” of the Imperial nation, here represented by the Ise Shrine in the upper panel.

In the effect, Tōgō was correct as the Japanese navy utterly destroyed the Russian navy in the battle and led to the end of the war. So the composition can be seen in these terms: that the naval victory of the bottom panel has led to glory of the Japanese nation, as represented by the upper panel.

The calligraphy is signed Heihachirō 平八郎, the name of Tōgō with which he signed his calligraphies, which became highly treasured.

Prof. Dr. Hans Bjarne Thomsen

From the Fūzoku gahō 『風俗画報』magazine, dated March 25, 1895

Part of the caption for the toy store image reads:

“In the image, a design from the war with China can be seen on the under-kimono (juban) worn by the customer in front of the shop, a person who has returned from cherry blossom viewing. The ground color of the design is red and includes features like [kabuki] actor portraits. Another example can be seen in the outer kimono of the beautiful woman with the design of sparrows and bamboo.

“In the image, a design from the war with China can be seen on the under-kimono (juban) worn by the customer in front of the shop, a person who has returned from cherry blossom viewing. The ground color of the design is red and includes features like [kabuki] actor portraits. Another example can be seen in the outer kimono of the beautiful woman with the design of sparrows and bamboo.

Both [of these designs] are available at the Daimaruya. Well-cultivated people with refined tastes should take notice [of our shop] when looking for objects reflecting current, popular themes.”

The shop mentioned above, Daimaruya, later became the Daimaru Department Store – this still exists today as one of Japan’s major department stores. The shop was originally established in the early 18th century.

#3

The Films

Besides the kimonos, the exhibition featured three feature films from 1936 to 1944 that contributed to the Japanese public’s education into a modern society with belligerent ambitions – a process that was not always conflict-free.

Akira Kurosawa, Ichiban utsukushiku [The Most Beautiful], 1944, 83 minutes

In the last years of the Second World War, women were recruited as volunteer helpers for the wartime economy. Kurosawa paints an ideal picture of this emergency in this propaganda film. Despite illness, exhaustion and personal misfortune, the young women insist on supporting the war with their labor.

The semi-documentary film was shot on location at the Nippon Kogaku factory in Hiratsuka. During production, the actresses lived like the factory workers they embodied on screen. Besides joint exercises and military parades, they also wore fujin hyōjunfuku, a simple, Western-style civil uniform introduced as official war clothing for women during the textile shortage in 1943.

Geijitsu Eigasha, Momotarō no Umiwashi [Momotarō's Seeadler], 1943, 37 Min.

Momotarō’s Sea Eagles is a Japanese propaganda anime that publically premiered in early 1943. The film features a protagonist known from Japanese popular mythology and was aimed at children. It depicts the human Momotarō recreating the attack on the US Navy base Pearl Harbor with an army of animals.

Kenji Mizoguchi, Osaka Elegy (1936), 71 min.

The image of Japanese women appears to have changed dramatically by the start of the 20th century. Young, unmarried women of the urban worker- and salaried class cultivated the “moga” lifestyle (derived from modan gāru oder “modern girl”). A typical “moga” went to work, cut her hair in a bob, wore Western-style clothing, smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol and amused herself with visits to bars and cinemas after work.

As Mizoguchi reveals in many of his films, this superficial transformation did nothing to break the deep, underlying patriarchal structures. Osaka Elegy follows the fate of a “moga“ named Ayako who gives in to her boss Mr. Asai’s advances so that she can pay off her father’s debts and provide for her brother’s education. Ayako behaves like a geisha from then on. She is financed by Mr. Asai, who not only gives her the necessary money for her family, but a modern apartment and new kimonos as well. When Asai’s wife catches on to the arrangement, Ayako – now dressed completely in Western-style clothing – sets out in search of another “patron.” This affair has a less fortunate outcome: As soon as Ayako has saved enough money and decides to leave him, he turns her in to the police. And that’s not all. Her family – who benefited from the proceeds of the prostitution business – want nothing more to do with the “fallen women.”

#4

The model of the Yamashiro-maru and Omi-maru

by Prof. Dr. Martin Dusinberre

The transformed world of 1900 would have been unimaginable to anyone born in 1800. The model you see embodied this new world: the Yamashiro-maru and Omi-maru were steamships, and thus represented the communication and transportation revolutions of the mid-late nineteenth century; and they were owned by a Japanese company.

Japan represented the transformations in world power that occurred in the nineteenth century. Until 1853, foreign access to Japan was limited to one international port, Nagasaki, and trade was limited to Dutch and Chinese merchants. Although Japanese political elites had some knowledge of world affairs in the mid-nineteenth century, especially the defeat of the once-mighty Qing Empire to Britain in the First Opium War (1839-1842), the arrival of an American naval squadron in 1853 was a profound shock. Two of the American ships were steam-powered, their engines belching black smoke and their paddle-wheels grinding through the water. They came to be known in Japanese history as the ‘black ships’, a phrase that encapsulated Japan’s extraordinary political, socioeconomic and cultural revolutions in the decades after 1853.

Yet only three decades later, Japan had its own ‘black ships’: the Yamashiro-maru and the Omi-maru. Both ships were built in Newcastle upon Tyne by Armstrong & Mitchell, one of the world’s most famous companies. Both were part of an order of sixteen new British steamships that Japan made in 1883-4 to build up the country’s merchant marine fleet (the suffix maru is given to non-military ships in Japan). At the same time, the Japanese navy placed orders for several new battleships to be built in British shipyards.

The Yamashiro-maru, the first and biggest of this new fleet, was for many years one of the most famous steamships of the Japanese merchant marine. ‘Yamashiro’ was the ancient province that included Kyoto, the imperial capital of Japan until 1868. In addition to sailing its regular line between Kobe and the new port of Yokohama, the Yamashiro-maru sailed to Hawai‘i on twelve occasions in the late-1880s and early 1890s; it was converted into a torpedo-carrier during Japan’s victory over Qing China in the war of 1894-95; it opened the new line from Yokohama to Melbourne in 1896; it served several routes in East Asia around 1900; and it was converted into a hospital ship during Japan’s victory over Russia in the war of 1904-05. The Omi-maru had a similarly diverse career.

In all these ways, the Yamashiro-maru and the Omi-maru exemplified Japan’s new engagement with the world in the late-nineteenth century, and Japan’s own emergence as an imperial power. The ships represented what contemporaries called Japan’s ‘progress’ on its journey towards ‘civilization’. But there are other journeys that can be told through the history of the Yamashiro-maru, such as the lives of thousands of poor Japanese labourers who emigrated to Hawai‘i in the 1880s and 1890s. Their voices are mostly silent, but their histories complicate the linear narrative of Japanese ‘progress’.

To recover these stories, to consider the transformation of the nineteenth-century world through material objects such as this model ship, to write world history from the sea and not just the land, to write non-linear narratives: these are challenges for the Jacobs Museum and for the new Chair of Global History at the University of Zurich. The presence of the Yamashiro-maru in the Jacobs Museum until 2018 reminds us of these challenges, and of the extraordinary technological and political transformations that continue to characterise our world today.

Lines meander across surfaces, drawing a picture of Japan’s territorial expansion. The three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning in the upper part are marked with gray and beige, while the Korean peninsula (colonized 1910) is kept a reddish brown. The discreet coloring traces back to the “48 brown and 100 gray tones” that Sen no Rikyū (1522-91) once propagated in terms of focusing on the essentials for the Japanese tea ceremony. The lines in turn show the rail network for the Japanese railroad company Mantetsu.

Lines meander across surfaces, drawing a picture of Japan’s territorial expansion. The three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning in the upper part are marked with gray and beige, while the Korean peninsula (colonized 1910) is kept a reddish brown. The discreet coloring traces back to the “48 brown and 100 gray tones” that Sen no Rikyū (1522-91) once propagated in terms of focusing on the essentials for the Japanese tea ceremony. The lines in turn show the rail network for the Japanese railroad company Mantetsu. The design of this kimono captures the drama and sense of awe that would have been felt when watching a squadron of bombers fly across the sky as they carry out a mission.

The design of this kimono captures the drama and sense of awe that would have been felt when watching a squadron of bombers fly across the sky as they carry out a mission.

The story of the three soldiers became a sensation in other media and within weeks, no fewer than five movies appeared in Japanese cinemas. Two appeared on March 3, another on March 6, another on March 10 and March 17. In addition to a multitude of books on the three soldiers, a number of other commercial goods appeared in stores:

the three soldiers now (posthumously) promoted their own candy, a hair conditioner, and a line of western-style clothing. And they of course also appeared on textile designs, as can be seen in the Ruf kimono. Their story and songs became a standard part of elementary school textbooks, at least until the end of the war. The theme also appeared in public places. An example is the bronze statue in a public park in Tokyo.

The story of the three soldiers became a sensation in other media and within weeks, no fewer than five movies appeared in Japanese cinemas. Two appeared on March 3, another on March 6, another on March 10 and March 17. In addition to a multitude of books on the three soldiers, a number of other commercial goods appeared in stores:

the three soldiers now (posthumously) promoted their own candy, a hair conditioner, and a line of western-style clothing. And they of course also appeared on textile designs, as can be seen in the Ruf kimono. Their story and songs became a standard part of elementary school textbooks, at least until the end of the war. The theme also appeared in public places. An example is the bronze statue in a public park in Tokyo. The calligraphy in the design is by the famous Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō 東郷平八郎 (1848-1934). The words are his command to his fleet at the climatic naval Battle of Tsushima of the Russo-Japanese War on May 27th, 1905. His actual words were: “This single battle will determine the glory or destruction of our imperial nation. Every person must give his utmost effort!” 「皇国興廃在比一戦各員一層奮励努力」.

The calligraphy in the design is by the famous Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō 東郷平八郎 (1848-1934). The words are his command to his fleet at the climatic naval Battle of Tsushima of the Russo-Japanese War on May 27th, 1905. His actual words were: “This single battle will determine the glory or destruction of our imperial nation. Every person must give his utmost effort!” 「皇国興廃在比一戦各員一層奮励努力」. “In the image, a design from the war with China can be seen on the under-kimono (juban) worn by the customer in front of the shop, a person who has returned from cherry blossom viewing. The ground color of the design is red and includes features like [kabuki] actor portraits. Another example can be seen in the outer kimono of the beautiful woman with the design of sparrows and bamboo.

“In the image, a design from the war with China can be seen on the under-kimono (juban) worn by the customer in front of the shop, a person who has returned from cherry blossom viewing. The ground color of the design is red and includes features like [kabuki] actor portraits. Another example can be seen in the outer kimono of the beautiful woman with the design of sparrows and bamboo.