#1

Sea voyage with uncertain outcome

“A Ship Will Not Come” is an exhibition devoted to the “sea voyage with an uncertain outcome” – which is not to say that an uncertain outcome necessarily has to be catastrophic. A ship might end up in a place you never intended to go, but where things are much better than you might have thought. Or the ship might not arrive to pick you up at all, and that’s fine, too. In other words, ships are associated with hope, but bad luck as well. And then there are of course the banal passages, the boring ones.

Exhibition View. Johann Jacobs Museum.

It was a happy coincidence that we stumbled upon film footage of voyages from the 1960s. 8mm film technology was the latest craze back then and facilitated the genesis of the so-called “home movie”. The footage has a certain patina: With its yellowed colors, the footage inevitably documents a world of yesterday when China was not yet a world power, Hong Kong had no skyscrapers, Ethiopia still had an emperor, the Cold War raged on, and the container ship had yet to be invented.

The footage itself was shot by sailors in the Swiss merchant navy, which was founded in 1941. The “flag of Switzerland” did not adorn many of these ships; in fact, the few that it did were intended to supply the otherwise landlocked continental state via its waterways in the event of a crisis. One of those flagged ships was the “MS Basilea” (built in 1952). This freighter with its almost 10,000 tons of load weight (transporting piece and bulk goods) sailed every sea in the decades after the Second World War. The “MS Basilea” crossed the Suez Canal and navigated the Congo, sustained fire during the Six-Day War off Port Said and waited at sea for weeks before it could pull into the Port of Luanda in an Angola shaken by civil war.

The “MS Basilea” footage is on the one hand a historical document. And yet the question also arises as to whether it is anything more than a “home movie” – a document intended primarily for private use that has no real place in a museum. The question as to at which point a document can claim a wider significance is not an easy one. When does the “tourist’s perspective” that this footage takes convey something like historical, political, or even an aesthetic insight? At which point does this external perspective shift to an internal one? The answer depends on the content of the document or the subject of the footage, but also on the form of its presentation.

MS Basilea Film Footage, (Freeze Frame), 1960s. Private Collection.

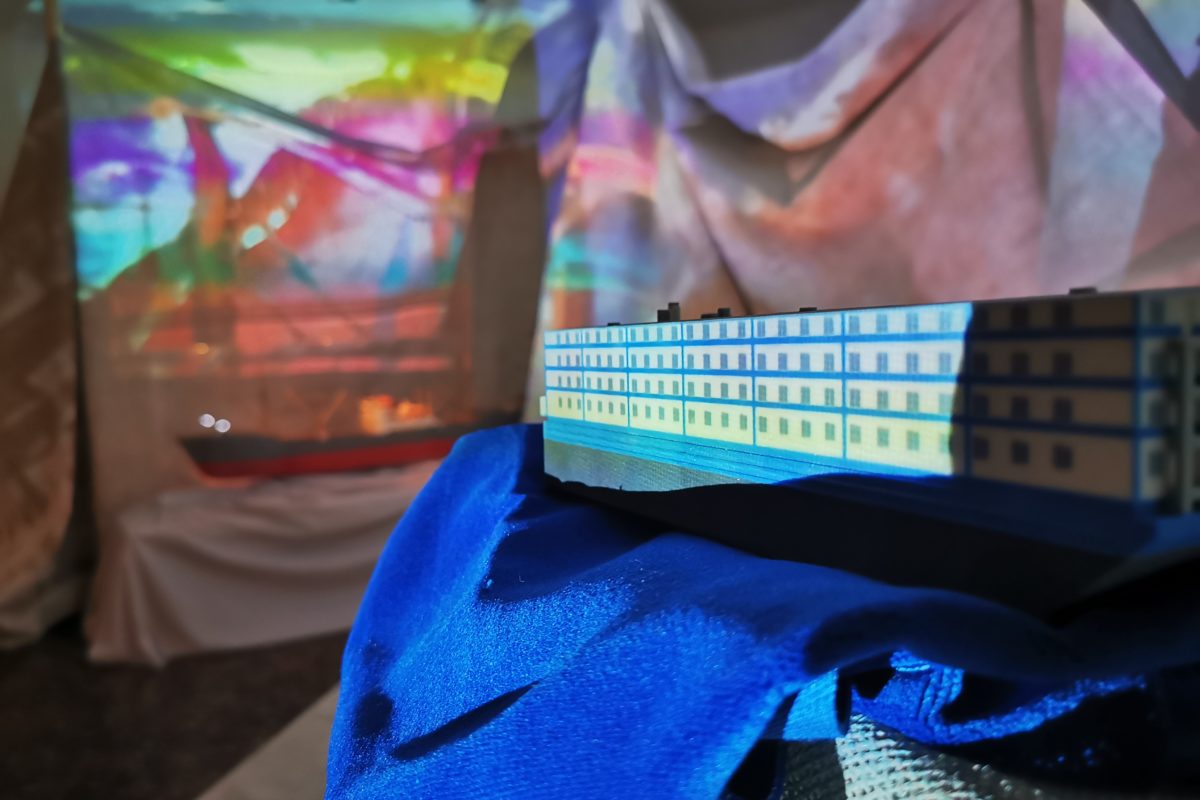

In this sense, our initial steps were to carefully edit the material, isolating those five episodes that we found worthy of closer examination. We also assembled images that capture the characteristic atmosphere of being at sea, which is to say the conjunction of waves, clouds, and rocking ship. Within the museum, these images are projected onto a large canvas spanning diagonally across the room – as if it were possible to walk through a painting.

The five mentioned episodes are briefly outlined here. They are: (1) a cinematic look through the porthole (views from windows are a perennial favorite in art history); (2) footage showing the loading and unloading of all types of goods; (3) the interaction with women who board in Bangkok, but also bring the sailors to their villages and families; (4) an aged emperor of Ethiopia’s visit to a Russian warship in the Port of Massawa; and (5) a parade in the Chinese port city of Dalian in the days of the Cultural Revolution.

MS Basilea Film Footage, (Freeze Frame), 1960s. Private Collection.

With the exception of the porthole, all of these episodes might be considered as having some historical importance. The ship’s crew never sought to create a grand historical narrative, of course; instead you could say that in looking at the footage, a viewer gains the impression that the sailors happened upon the situations by coincidence (the imperial visit to Massawa, for example). Their life at sea seems characterized by a curious mixture of desire (the Thai “girlfriends’” visit), opportunities (the shipping of water buffalo to Hong Kong), or privileges (being allowed to go ashore during the Cultural Revolution in China and filming a parade). “Coincidence”, “desire”, “opportunities”, and “privileges” are also key concepts when it comes to grasping the course of this history with a capital “H”.

Complementing the exhibited “MS Basilea” footage are various artistic works related to the theme of ships or ships’ passage. One might say our arrangement resembles a meeting of ships on the wide expanse of the ocean or within the enclosure of a harbor.

Approaches to historical truth

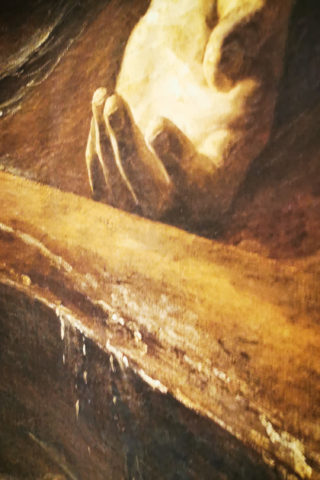

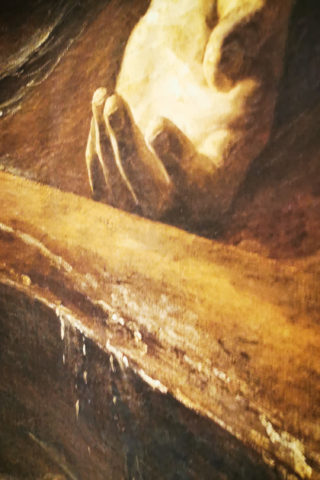

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, oil on canvas, 1819. Louvre Collection, Paris.

A serious ship disaster occurred off the coast of Senegal in 1816. The frigate “Medusa” had run aground. Its captain and the officers of a contingent of French colonial troops fled to the lifeboats. The remaining crew, about 150 people, drifted for nearly two weeks on a hastily-assembled raft with no significant supplies. The lifeboats had originally intended to tow the raft behind them, but the sea became too stormy and the captain was forced to sever the connecting rope. Scenes that took place on the raft – including acts of cannibalism – are beyond imagination. Fifteen of those people were still alive by the time they were rescued.

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, oil on canvas, 1819. Louvre Collection, Paris.

The raft’s fate drew a great deal of European media attention at the time. French painter Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) was so moved by the account of one survivor that he devoted a monumental canvas to its rendering. “The Raft of the Medusa” (1819) sparked a massive scandal upon its first showing but hangs as a masterpiece in the Louvre today.

It wasn’t necessarily the fate of the man that inspired Géricault’s painting per se; it had more to do with political fiasco, more precisely the failure of a corrupt elite that had regained power with the restoration of the monarchy in France and had actively participated in the slave trade, among other things. For all its drastic realism (the painter went so far as to obtain body parts from the morgue for study), “The Raft of the Medusa” remains an allegory of “bad government”.

Not a Seascape

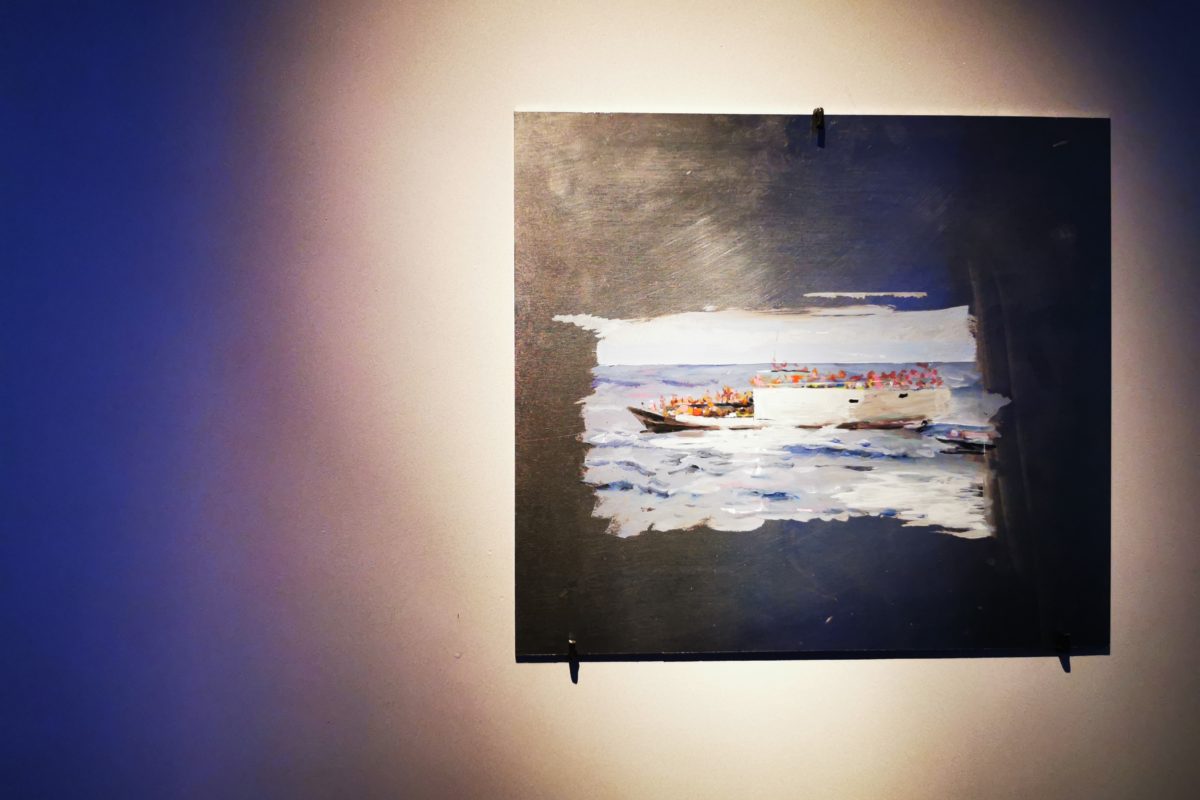

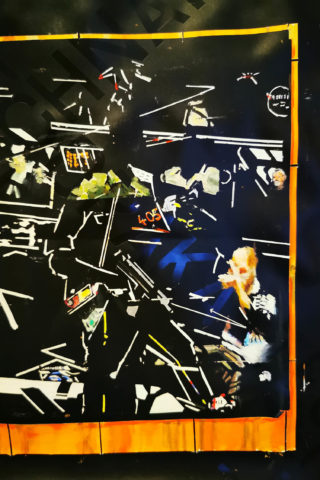

Dierk Schmidt, Xenophob – Shipwreck scene, dedicated to 353 drowned asylum seekers in the Indian Ocean, October 19, 2001, in the morning; oil on acrylic on PVC film, from the cycle SIEV-X – On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics, 2001/02. Courtesy of the artist.

Conscious of the refugee catastrophes that are currently taking place on the oceans, painter Dierk Schmidt set about transferring Géricault’s approach to suit the present. It is not a 1:1 translation, as there is no need to reimagine today’s inflatable rubber boats in the role of the kind of raft available back then.

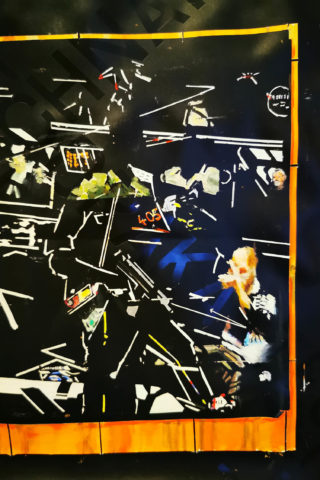

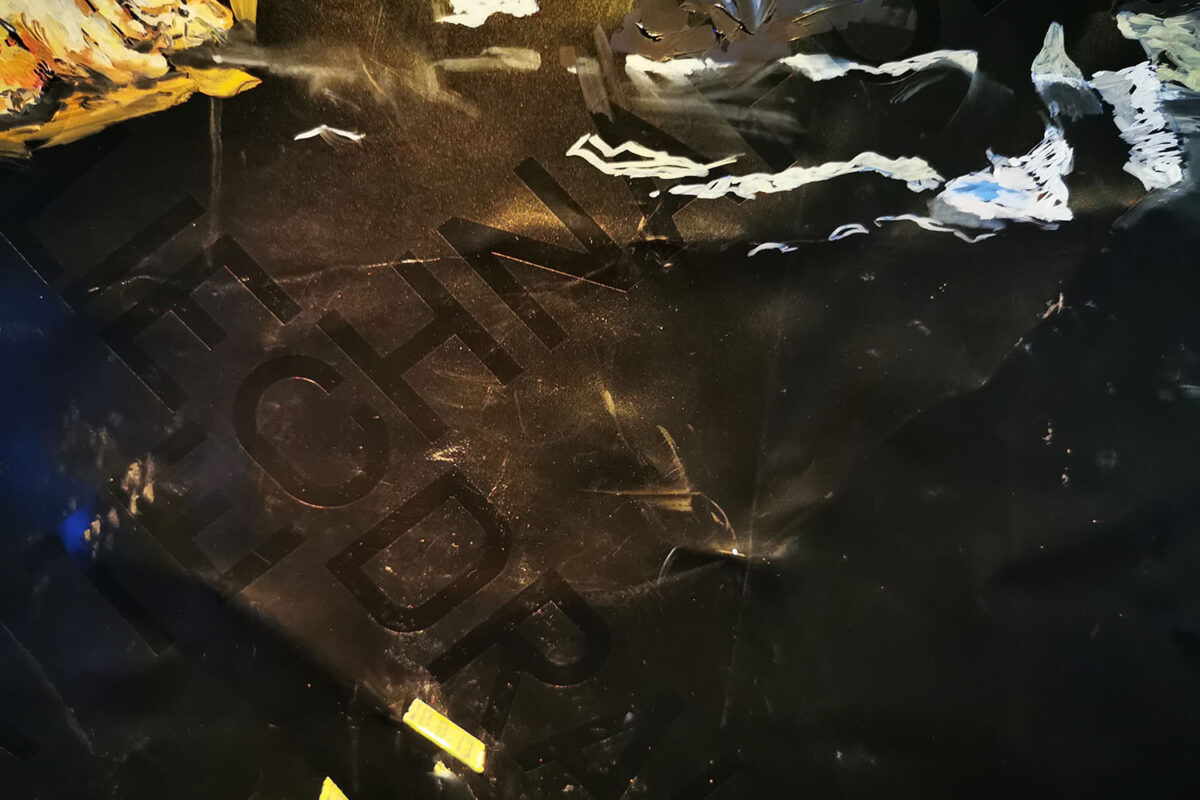

Schmidt’s cycle “SIEV-X – On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics” (2001–2003) uses a kind of painterly abstraction that makes structures visible. It deals with the power structures underlying catastrophes at sea: the ominous mixture of traffickers, economic dependence, border regimes, wealth gaps, lawlessness, bureaucratic operational plans and political calculations – all enriched with individual empathy, indifference or cynicism. Can power structures like the ones linking Libya and the European mainland today, or in Schmidt’s case the Indonesian archipelago and the Australian coastguard, or with Géricault, the French royal court and colonial Senegal, be depicted at all? Can they be painted?

Schmidt’s cycle “SIEV-X – On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics” (2001–2003) uses a kind of painterly abstraction that makes structures visible. It deals with the power structures underlying catastrophes at sea: the ominous mixture of traffickers, economic dependence, border regimes, wealth gaps, lawlessness, bureaucratic operational plans and political calculations – all enriched with individual empathy, indifference or cynicism. Can power structures like the ones linking Libya and the European mainland today, or in Schmidt’s case the Indonesian archipelago and the Australian coastguard, or with Géricault, the French royal court and colonial Senegal, be depicted at all? Can they be painted?

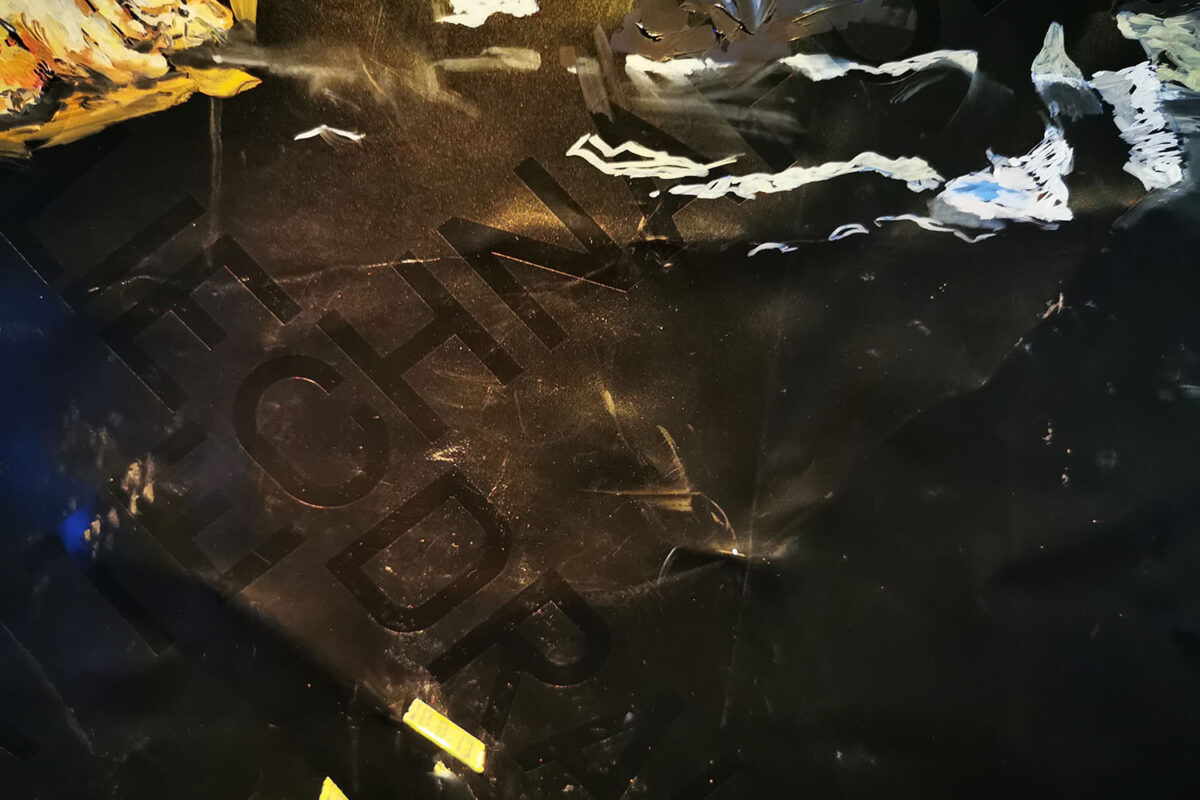

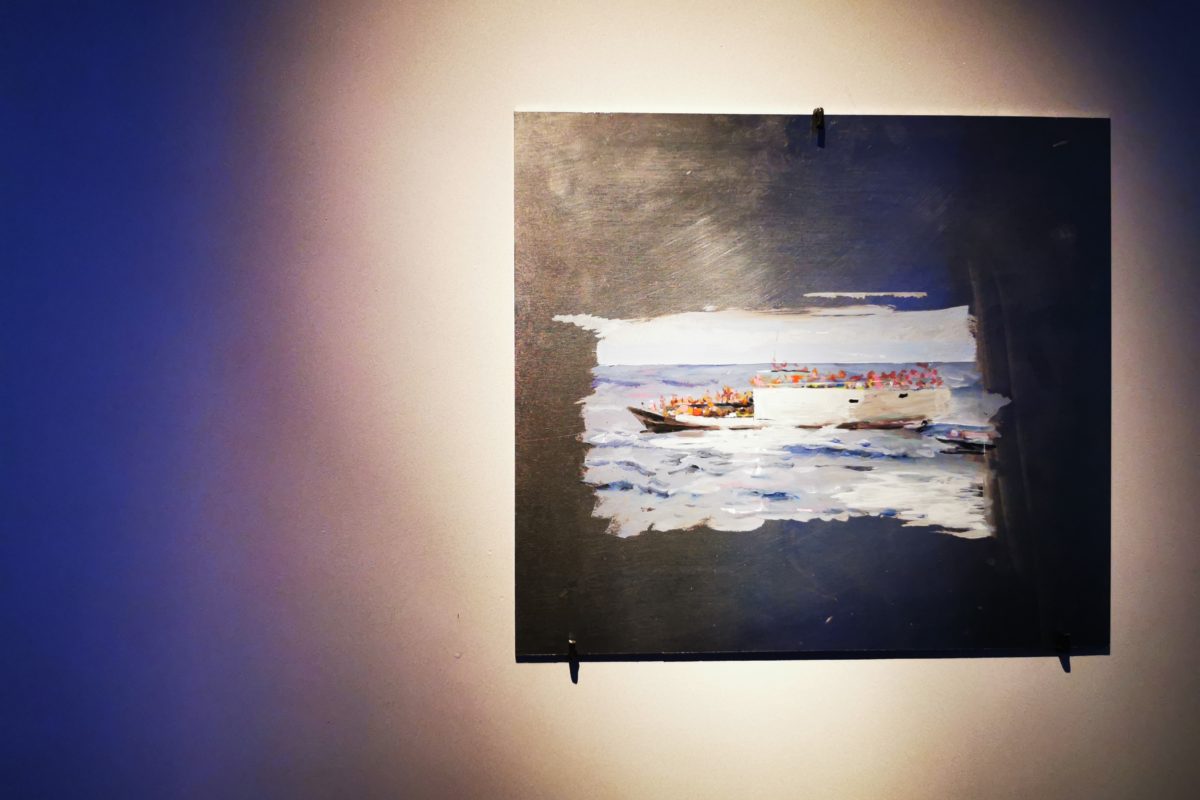

Dierk Schmidt, Not a Seascape (II), Oilsketch from the Picture Cycle SIEV-X, 2001-2003. Courtesy of Ruth Noack.

Géricault knew what he had to paint, and he knew how. There were eyewitness accounts of the disaster on the raft. The painter had even contacted survivors and consulted with them in the studio. But how do you paint a ship that capsized on the crossing from Indonesia to Australia, a vessel for which there is no documentation? The small aluminium panel shows Schmidt’s preliminary study of a random refugee boat painted from a newspaper photograph. He chose a black background for the “real”, albeit invisible ship, so that invisibility becomes to a certain extent the image carrier, or the condition, of the painting. He then paints signs on this black background: faces, radar signals, parts of the railing, a machine gun (used to force the refugees onto the boat in Indonesia). Everything remains vague until the viewer’s gaze begins to develop the picture further. Gradually, the painting completes itself in the eye of the beholder.

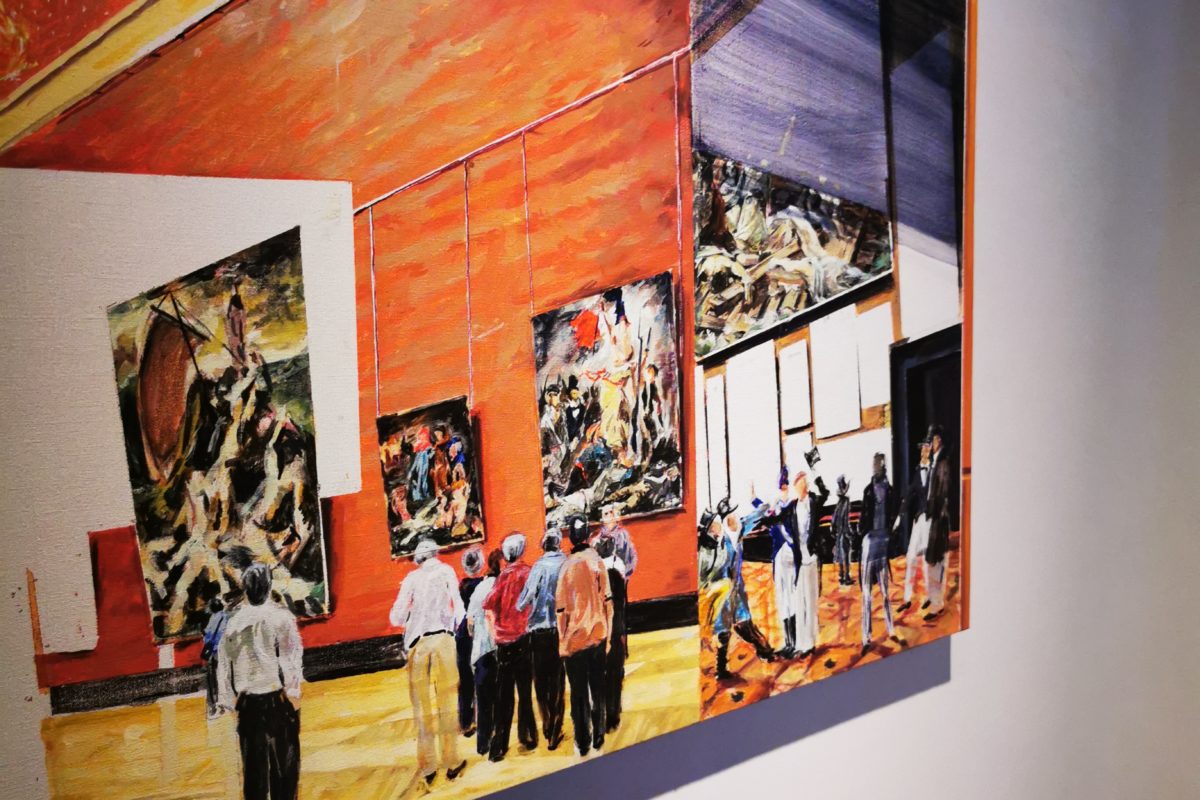

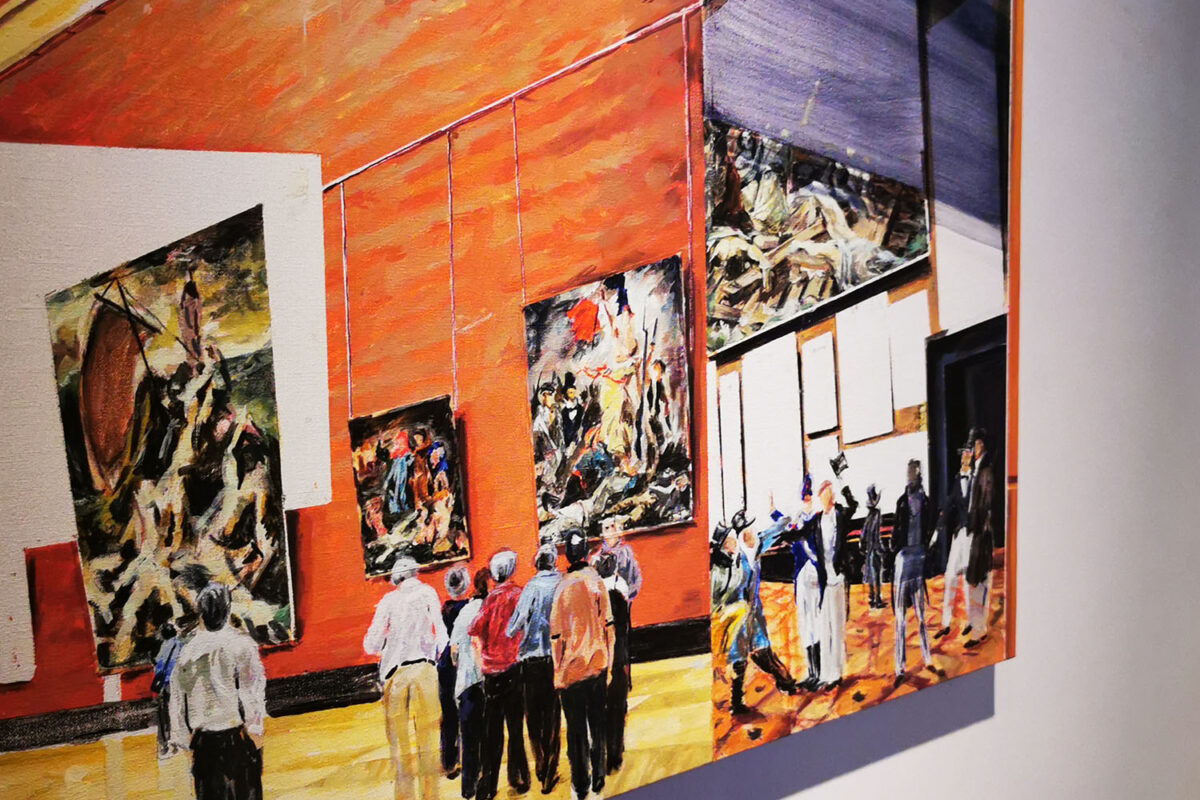

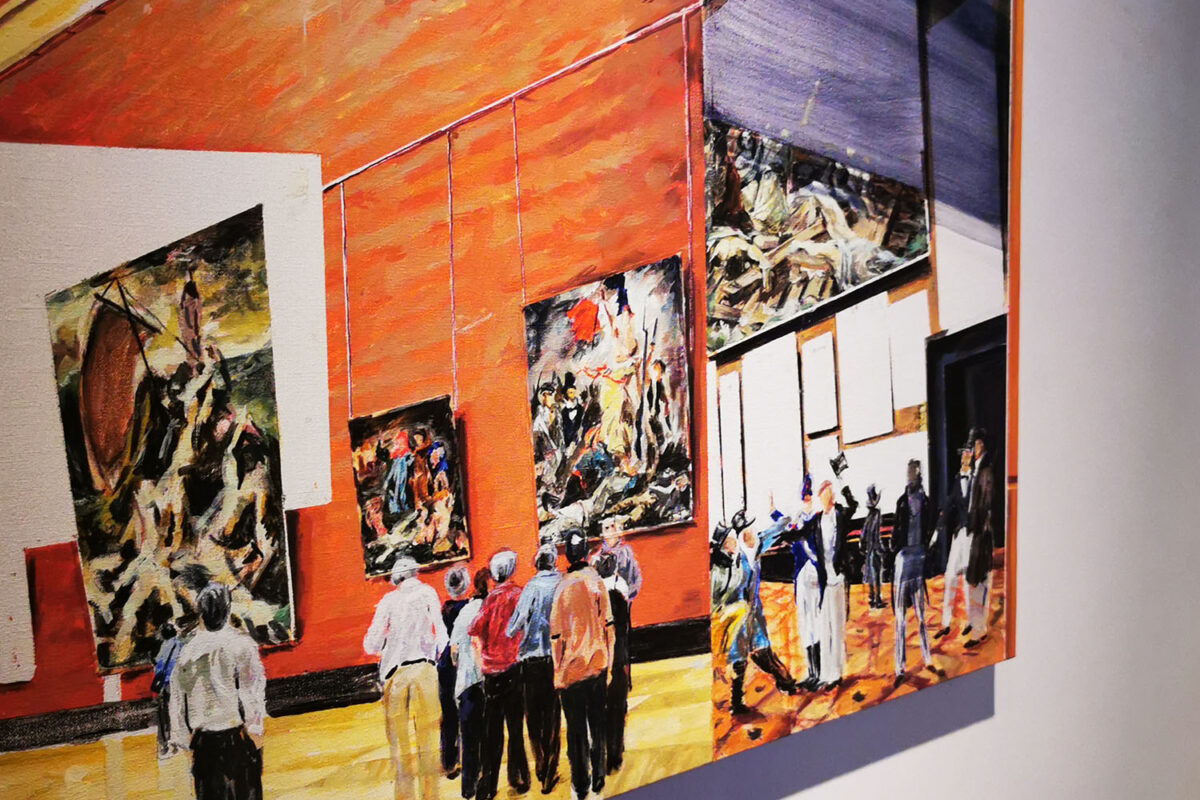

Dierk Schmidt, work detail, Untitled (Salon Carré 1819 / Louvre 2001/02), oil on canvas, middle part of a triptych from the picture cycle SIEV-X - On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics,

2001/02. Courtesy of the artist.

Dierk Schmidt, work detail, Untitled (Salon Carré 1819 / Louvre 2001/02), oil on canvas, middle part of a triptych from the picture cycle SIEV-X - On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics, 2001/02. Courtesy of the artist.

Dierk Schmidt, Not a Seascape (II), Oilsketch from the Picture Cycle SIEV-X, 2001-2003. Courtesy of Ruth Noack.

Dierk Schmidt, Xenophob - Shipwreck scene, dedicated to 353 drowned asylum seekers in the Indian Ocean, October 19, 2001, in the morning; oil on acrylic on PVC film, from the cycle SIEV-X - On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics,

2001/02. Courtesy of the artist.

Exhibition View, Johann Jacobs Museum.

Previous

Next

Dierk Schmidt’s picture cycle “SIEV-X: On a Case of Intensified Refugee Politics” is extremely extensive and now forms part of the Städel Museum’s collection in Frankfurt am Main. This exhibition presents three studies the artist executed as part of his research. The oil painting (left) shows Schmidt contrasting two hangings of Géricault’ “The Raft of the Medusa”: The first is the painting’s original hanging in the Salon of 1819 in Paris, where the scandalous image was hung high (just below the ceiling), and the current hanging (also seen in one of the videos shown in this exhibition).

Bibby Challenge

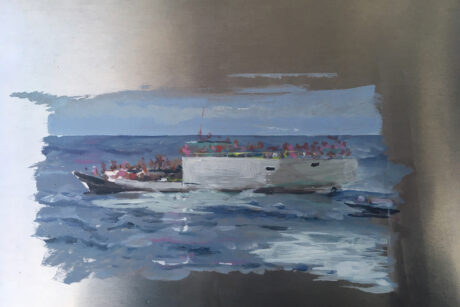

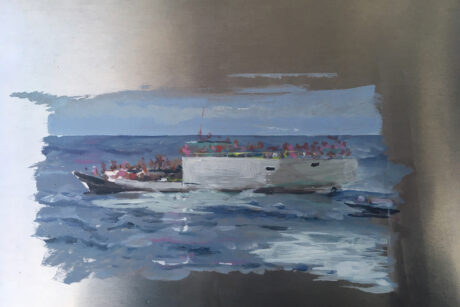

Adnan Softić, Bibby Challenge, photograph, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

The “Bibby Challenge” – a cross between a cruise ship and container ship – is a kind of improvised home on the water that German authorities in Hamburg set up to accommodate refugees from the Yugoslav Civil Wars.

Adnan Softić, Bibby Challenge, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

The artist Adnan Softić lived on this ship, which was anchored in the middle of the city on the river Elbe. On the one hand Softić’s installation reconstructs the particular way of life on the ship in sounds and images, its gentle rocking reminding those who lived there of the provisional nature of their accommodation from the moment of their waking until they fell asleep again at night. And yet it also situates the “Bibby Challenge“ phenomenon in a general topology of ships and ship passages. Softić addresses the ship as both a place and a non-place at the same time – as a floating, highly mobile vessel that knows how to navigate the boundaries between national and international waters, if only because twothirds of the Earth’s surface is covered with water.

Vorstellung von einem Land (Eweland)

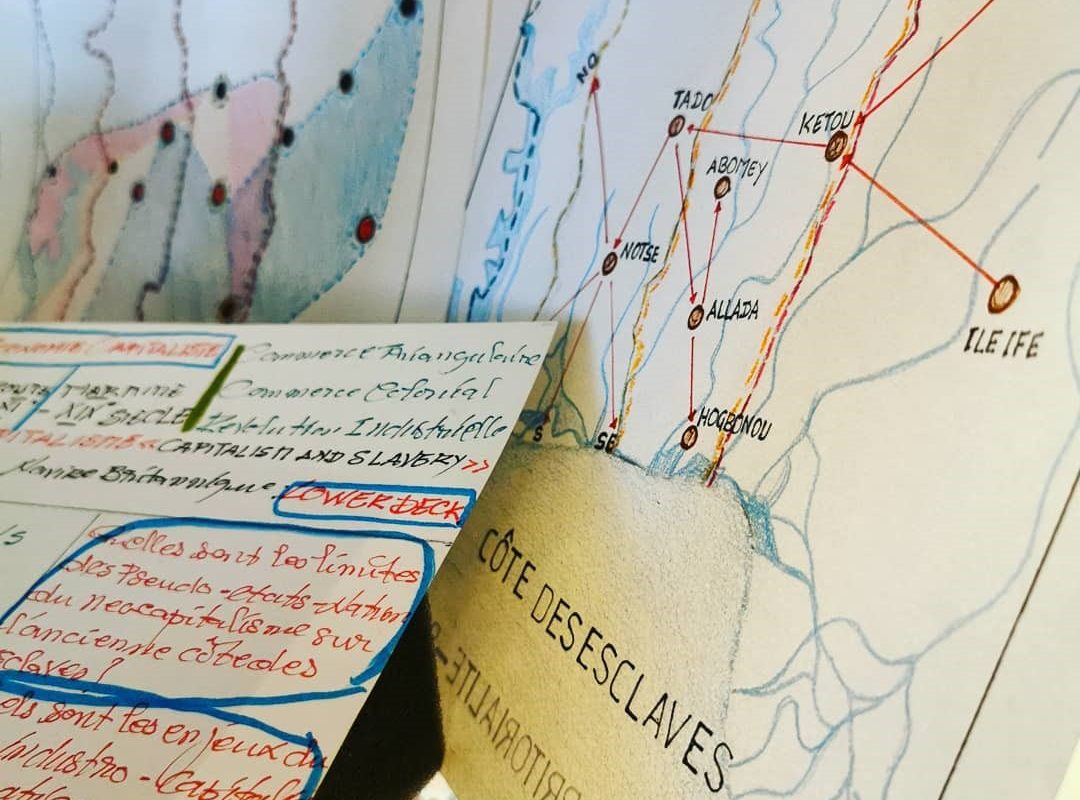

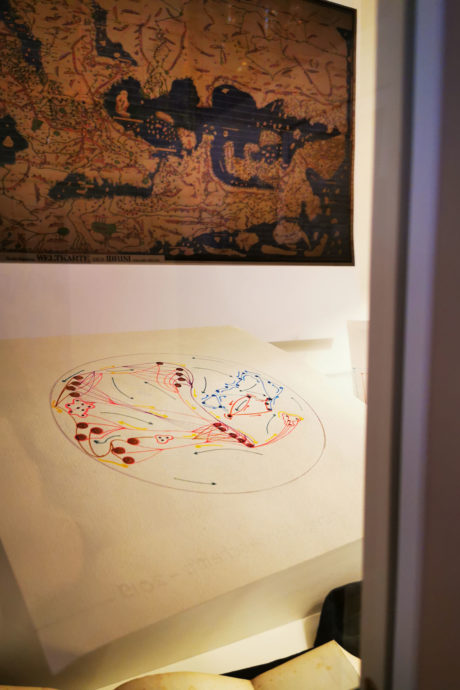

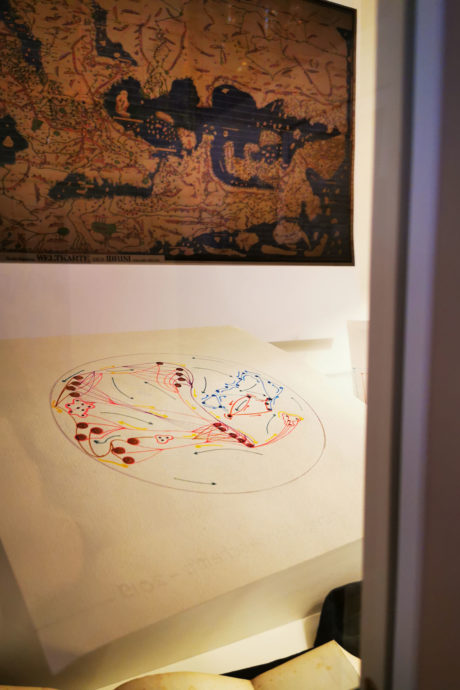

Eza Komla, Territorial Imaginaries (Eweland), drawing on paper, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

The colorful drawings of Eza Komla are attempts to gain better insight into both historical and current migration and deportation routes and the flows of goods that connect and have connected the African continent with Asia, Europe and the Americas for centuries. The artist’s particular interest lies with the Ewe people. The Ewe live along the former “slave coast,” a space that spans across today’s nation-states of Benin, Togo, and Nigeria. The Ewe have had to endure various colonial regimes: German, French and British. While a variety of scattered existences makes it unclear whether the story of a people like the Ewe can even be told, this is precisely what Eza’s artistic cartography sets out to do.

Eza Komla, Territorial Imaginaries (Eweland), drawing on paper, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

The drawings of Eza Komla are sketches, reflections, or models that help visualize an extremely complex situation: that of the Ewe, a people primarily settled around the Volta River (in present-day Togo). The transatlantic slave trade and various colonial regimes were keenly felt by the Ewe, who were abducted, scattered, deported and resettled as a result. Eza’s drawings are tentative and subtle; they convey less a big message or larger narrative than something like a soliloquy around the (artistic) question, “How should I portray something”?

Hanging next to Komla’s cartographic studies is a famous map of the world, the “Tabula Rogeriana” (lit. “The Map of Roger” in Latin, a reference to Norman King Roger II of Sicily). Arab geographer Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti – al-Idrisi for short – drew this map over many years at the court in Palermo, until it was finally completed in 1154. The “Tabula Rogeriana” renders the entire Eurasian continent and North Africa in a way that seems rather unfamiliar to us today. The location names and descriptions were written in Arabic; the original has not been preserved. The open book is the “Voyage dans les Quatre Principales Îles des Mers d’Afrique [Journey to the Four Main Islands of the African Continent]”, which dates from the first years of the 19th century. The book is sort of a directory; it describes the African continent as a resource-rich terrain waiting to be exploited.

La casa degli altri

Dias & Riedweg, “La casa degli altri” (The House of the Others) (Freeze Frame), two-channel video installation, 2017. Courtesy of the artists.

A street scene near Roma Tiburtina, the second largest railway station in Rome. Protected by a stately pine, African refugees have set up camp. They cook, hang laundry to dry, attend classes at (provisional) school desks and play football. The place is badly neglected, with old mattresses and broken prams strewn about, in short: Western garbage. And yet it seems the newcomers know how to use and reuse these things. Time flies; mighty flocks of birds traverse the sky; birds know no bounds.

Dias & Riedweg’s perspective on this makeshift habitation resembles that of the Swiss sailors. The camera observes and captures but does not attempt to infiltrate the scene. Henri Dunant (1828–1910), founder of the Red Cross, spoke of his “tourist’s perspective” in 1829 while taking in the battlefield of Solferino in Northern Italy with its whimpering wounded and dead. It was that very experience that drove the entrepreneur to social activism and contributed to one of the greatest myths of the Swiss state: that of a humanitarian mission that attends to not one, but both sides of a conflict while remaining neutral.

All That Perishes At The Edge of Land

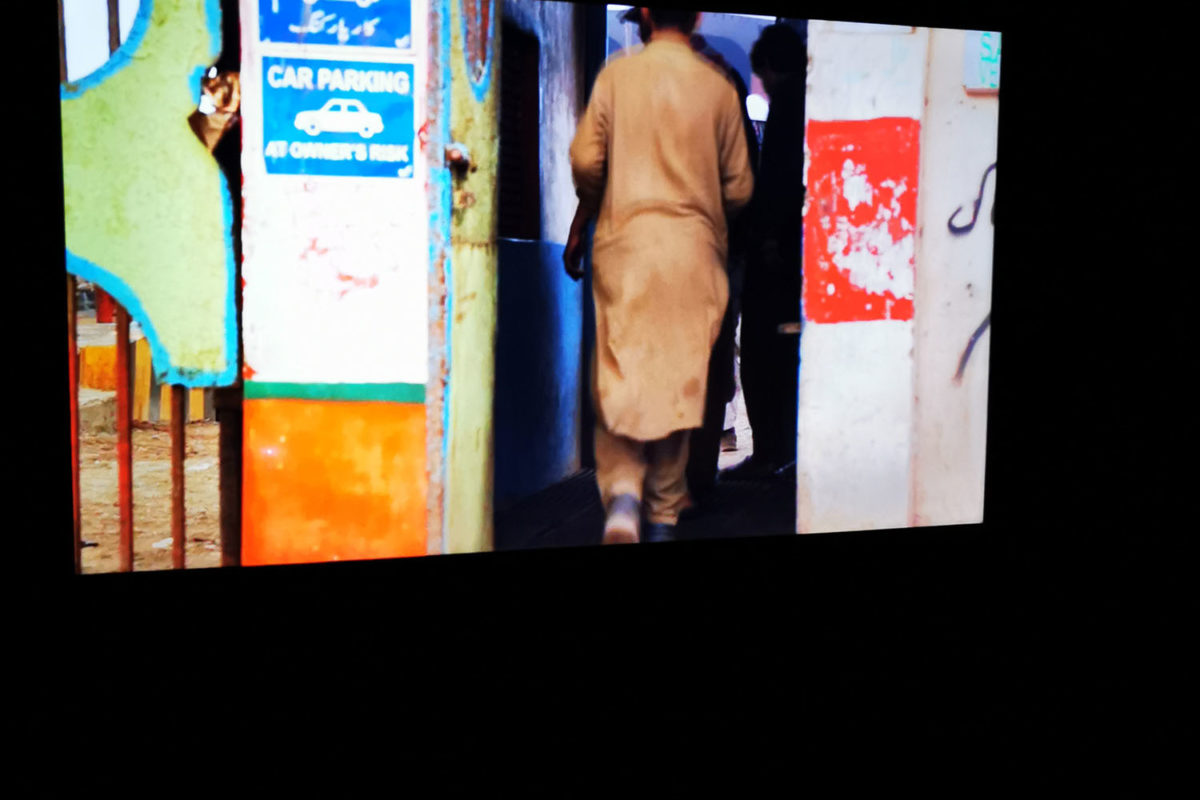

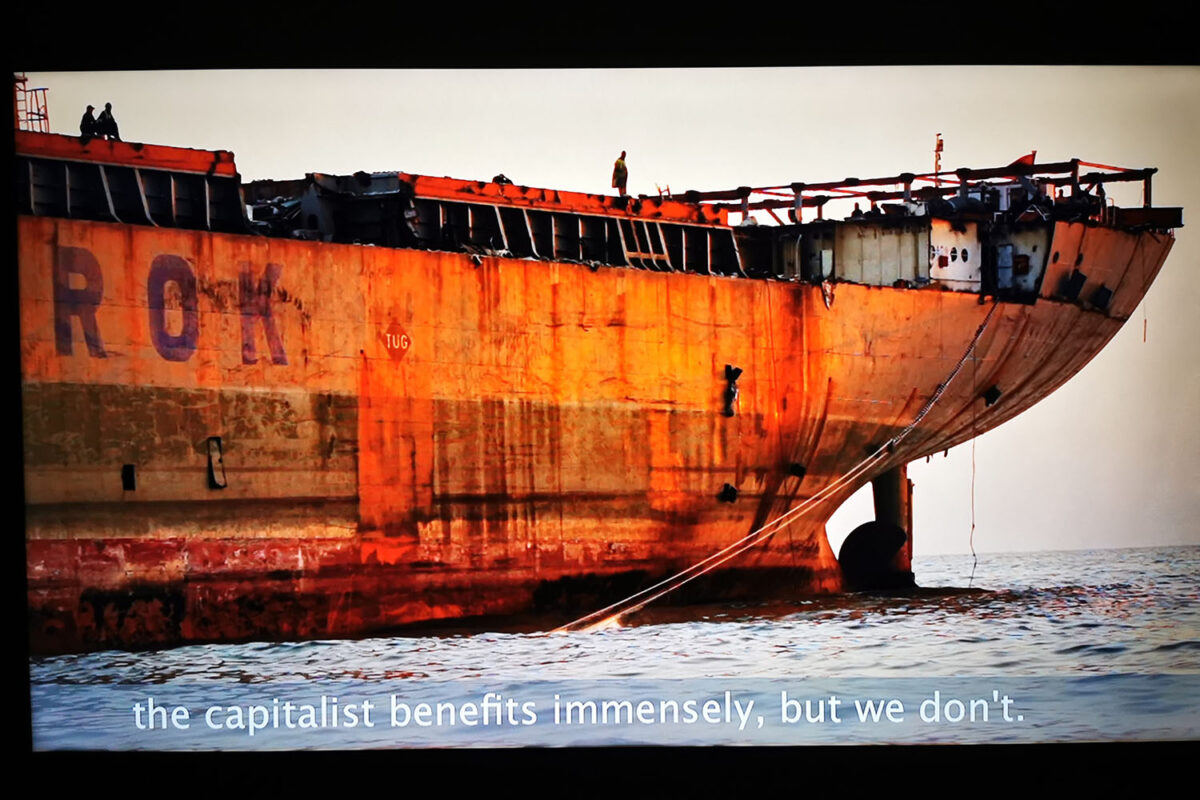

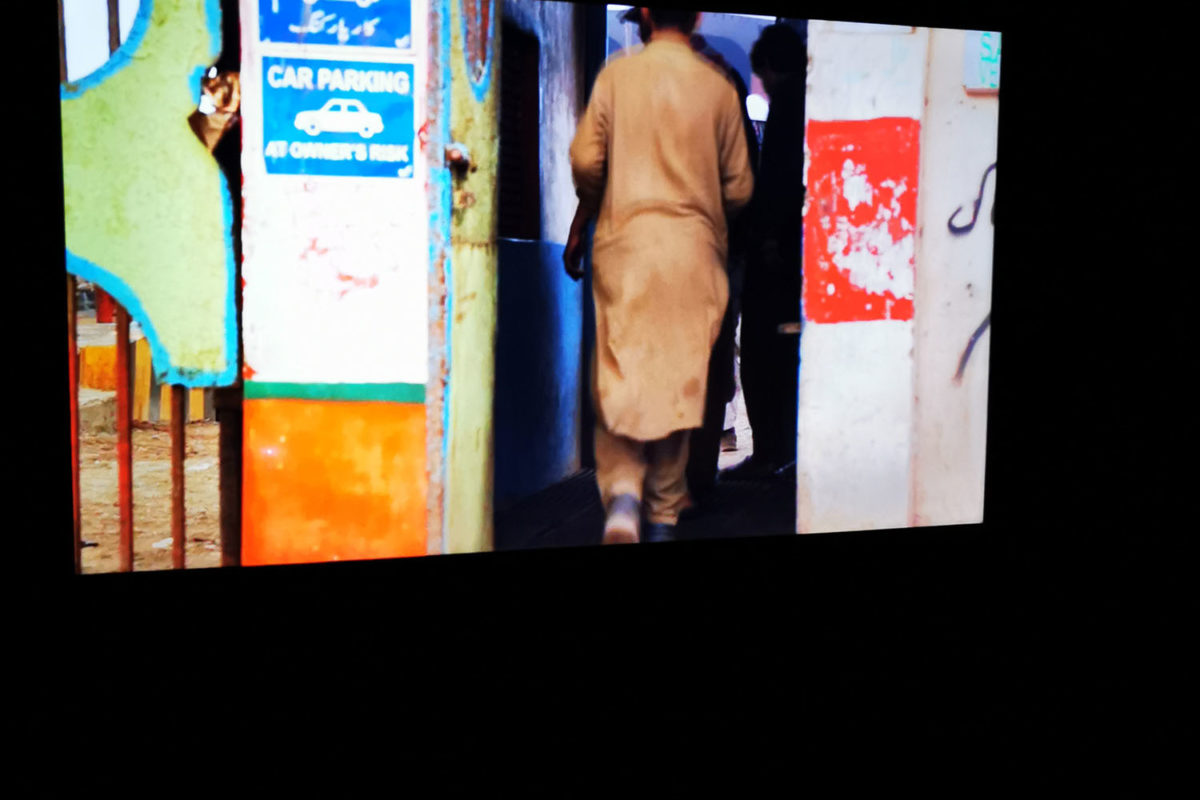

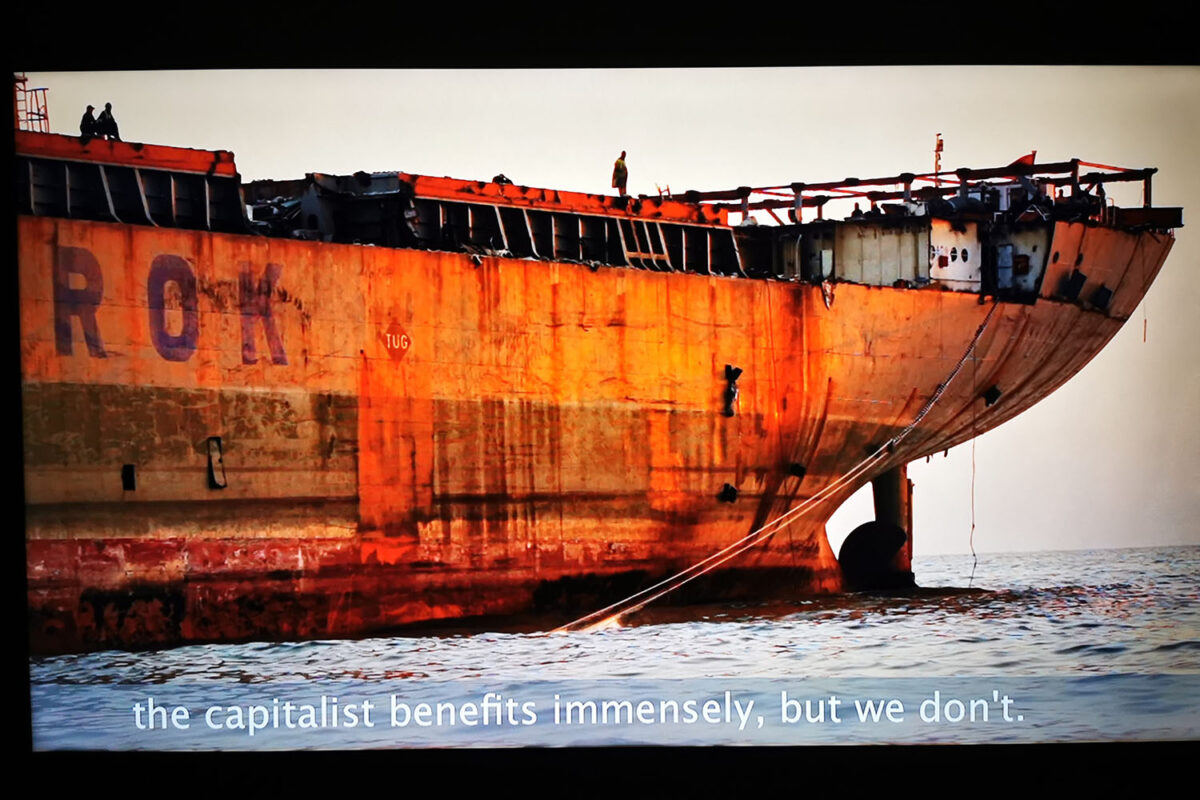

Hira Nabi, All That Perishes At The Edge of Land, (Freeze Frame), documentary feature film, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Hira Nabi, All That Perishes At The Edge of Land, (Freeze Frame), documentary feature film, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Hira Nabi, All That Perishes At The Edge of Land, (Freeze Frame), documentary feature film, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Martin Hurley, Bangladesh Scrapping Yard, photograph, Chittagong, 2003. Courtesy of the artist and Alamy Stock Photo.

Hira Nabi, All That Perishes At The Edge of Land, (Freeze Frame), documentary feature film, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Previous

Next

The cities of Chittagong (Bangladesh), Gujarat (India) and Gadani (Pakistan) have informal ship cemeteries where monumental tankers and container ships are scrapped or, more precisely, disassembled into their individual parts. This is only possible with the help of collective manual work which, as one can imagine, happens under extremely precarious conditions with poor pay and serious ecological costs. Still usable materials such as copper are returned to the global commodity cycle, meaning they do not benefit the country itself (in this case, Pakistan).

The contrast between the furious hammering and hissing of welding torches at Gadani shipbreaking yard and the little porcelain bowl from Meissen (18th century) could hardly be greater, and yet the two are more closely related than one would think. The bowl shows the loading of cargo from junks to huge sailing ships, perhaps at the mouth of the Pearl River where the colonial port city of Hong Kong would soon come into being.

Exhibition View. Johann Jacobs Museum.

Hira Nabi, All That Perishes At The Edge of Land, (Standbild), Doku-Film, 2018. Mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Künstlers.

Previous

Next

Saigō Takamori and the Modernisation of Japan

Legend has it that old Japan ended in 1853 with the arrival of US Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” in the Bay of Edo (now Tokyo Bay). Under the mild threat of armed force, the Western powers forced Japan to open its ports for trade. With the colonization of China at the forefront of their thoughts, the Japanese had no doubts as to the gravity of the situation.

Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, The Suicide of Saigo Takamori, (Saigo Takamori Seppuki (no) Zu, color woodblock print, Oban Triptych, Japan, 1877. Collection Johann Jacobs Museum, Zurich.

In an unparalleled act of political will known as the “Meiji Restoration” (which was actually a revolution), the country’s elite decided to radically modernize almost all aspects of Japanese life. Military technology played a key role in this process.

Saigō Takamori is considered the “last great Samurai”, or the last scion of a warrior caste that fell victim to modernization. Originally an important advocate of the “Meiji Restoration”, Saigō gradually grew alienated with the reform process. He retired to his native Satsuma Province, and it is there that he launched a rebellion against the government that was eventually crushed. All sorts of rumors circulated about his death. Artist Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1835–1892) – also a “last great”, in this case of the Japanese printmaking-artists – depicts Saigō’s demise with a scene befitting his status: a ritual suicide.

Exhibition View. Johann Jacobs Museum.

The military modernization of Japan as a consequence of the “Meiji Restoration” culminated in the December 1941 destruction of the United States Pacific Fleet stationed in Hawaii. The Japanese had already decimated Russian Empire forces as early as 1904/5, in a war ignited over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and Korea. This defeat shocked observers in the West. This video by Montemajor describes the attack on Pearl Harbor from a Japanese perspective.

Program Cultural Revolution

MS Basilea Film Footage, (Freeze Frame), 1960s. Private Collection.

Five hundred tons of beans, a load of musical instruments, playing cards and one hundred fifty tons of human hair were destroyed when the “MS Basilea” collided with a Russian tanker in 1973. The destroyed ship cargo had come directly from Shanghai – one of the five treaty ports that had been opened in 1842 after the city’s British occupation during the First Opium War. The former fishing village on the Yangtze River Delta was carved into autonomous concessions overseen by the French, British and Americans – a colonial presence that transformed the city into a hub of migration, industry and trade. But in the 1960s and 1970s, just as the “MS Basilea” and its crew were moving in and out of Chinese and Southeast Asian ports and through the streets of Shanghai itself – China was in the throes of cultural revolution. Cities like Shanghai bordered on total anarchy. The ideas behind the Cultural Revolution – a broadly-conceived political effort that served to strengthen Mao’s authority – were to uproot imperialist, decadent and corrupt bourgeois elements from Chinese government and society, to revive the

MS Basilea Film Footage, (Freeze Frame), 1960s. Private Collection.

revolutionary spirit that had fueled the civil war just decades before and to purge Chinese society of the so-called “Four Olds”, or the pre-communist elements of Chinese society: old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas. Although Mao had sketched out these revolutionary ideas as early as the 1920s, he had only been able to implement them in a limited way until that point. One year after Mao closed the nation’s schools and called on the nation’s youth and factory workers to take on party leaders and elements of society that opposed him or the socialist ideals of the CCP in 1966, a crew of Swiss passengers disembarked from the “MS Basilea” in Dalian and witnessed the carefully choreographed demonstrations of political ritual and legitimization – in the form of a parade. A certain continuity can be observed in the grandiose representation of China in this parade and the recent celebration commemorating the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. One big difference is that the trains and planes of 1967s modernity were constructed out of cardboard, in striking contrast to the hypersonic drones and intercontinental ballistic missiles in China’s recent military parade.

Zwischen den Frontlinien: Massawa

Ethiopia – or rather the idea of it – took on a whole new meaning after Mussolini’s invasion and occupation of the Ethiopian Empire in 1935. “Ethiopia” had until then been more of an idea – the seat of a historic Black empire steeped in legend, supposedly descended from the union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Now, under pressure from the military invasion, the notion of it shifted from abstract signification to a more concrete place – the site of a struggle for African unity and emancipation from Western oppressors. Ethiopia (or Abyssinia as it was then called) first drew attention as an exceptional African Empire after the Battle of Adwa in 1896 – one of the most spectacular African victories over a European power (Italy). Its exceptionality lay not only in its long dynastic history and early Christian culture, but increasingly in the figure of its emperor: Haile Selassie.

MS Basilea Film Footage, (Freeze Frame), 1960s. Private Collection.

Selassie’s coronation in 1930 set off an iconographic storm with somewhat hagiographic undertones that spread across the Atlantic, inspiring followers from Jamaica to New York City’s Harlem. The global Great Depression hit the African diaspora particularly hard, and Haile Selassie (born Ras Tafari Makonnen) became inextricably entwined with the emerging Rastafari movement in Jamaica. This religious movement (with Bob Marley as its most prominent proponent) saw Selassie as a messianic figure of redemption who promised peace and prosperity. Images of Haile Selassie were revered as icons in Jamaica, but they held more than just spiritual power. They also had worldly influence; a picture of Selassie could supposedly serve as a ship-passage ticket to Massawa – a Red Sea port that the United Nations had granted the Ethiopian Empire in the 1950s, following the federation of otherwise-landlocked Ethiopia and Eritrea. It was here in Massawa that Selassie would establish the Imperial Ethiopian Navy in 1955. It is also where he would encounter the crew of the “MS Basilea”.

Bo’sun betätigt die Seilwinde

Allan Sekula, Bo’sun Driving the Forward Winch, cibachrome print mounted on dibond, wood frame, 1993. Collection Johann Jacobs Museum.

Artist Allan Sekula (1951–2013) devoted years of his life to the ocean and maritime activity. His travels, photographic and filmic reports, all combined with essayistic texts, culminated in the opus magnum “Fish Story” (1995), one of the most important artistic works of recent decades. The photograph shown here, entitled “Bo’sun Driving the Forward Winch” (1993) comes from “Fish Story”, Sekula’s documentary on the “sea as the forgotten space of modernity”. The photo recalls the same types of people (“baker”, “the sailor”, etc.) that German photographer August Sander recorded in the “Anlitz der Zeit [Face of Time]” (1929). While Sander was more interested in capturing the sociological situation of individuals and their role in modern society, Sekula allows his “model” liberties: Bo’sun, sandwiched between machines, shifts and controls, also turns his back to us.

Thurgau - Brasilien

Willhelm Gaensly, European immigrants pose for a photograph in the central courtyard of the Hospedaria dos Imigrantes in São Paulo, photograph, 1890, São Paulo. Collection Fundação Patrimônio da Energia de São Paulo – Memorial do Imigrante.

Wilhelm Gaensly (1843–1928) was born in the canton of Thurgau and emigrated to Brazil as a child with his family. He first lived in Salvador, where he was apprenticed to a portrait photographer. When the coffee boom hit Brazil in the 1890s, Gaensly moved his studio to the rapidly growing metropolis of São Paulo. He is famed for his landscape panoramas of coffee plantations, documentation showing the advent of modern infrastructure (i.e. railway construction and electrification), and his group photographs of Italian immigrant families arriving in Santos (the port of São Paulo). The group picture here is an example of the latter that leaves room for spontaneous moments: While the barefooted girl in the foreground on the left ventures further toward the camera than the skeptical adults, the play of her hands reveals a certain embarrassment when confronted with such a completely new situation on a foreign continent. The bickering boys (on the right in the picture) are more interested in their own interaction than in the photographic moment, which was not as commonplace then as it is today.

Dampfmaschinen und Rohstoffe

Alfonso Bialetti developed the caffettiera in the early 1930s. The device is a little steam machine and thus at least metaphorically related to the driving forces of the Industrial Revolution. Both its material (an aluminium alloy) and form suggest an extension of modernity’s reach into the individual household, where the pot’s contents put a little extra spring in peoples’ step. The Meissen sculptural groups made of porcelain have a completely different tempo, showing something more like aristocratic inertia or, to put it more politely, leisure. “Indian Lovers” (early 18th century) by Johann Joachim Kaendler shows a man and woman engaged in tender banter with mandolin, parrot and chessboard (upon which the woman rests her foot). The word “Indian” in this case refers to anything beyond India, including the Japanese flowers on the woman’s kimono and the man’s “Chinese hat”. The aristocratic lady, wearing a yellow bow on her chest that identifies her as a Freemason, is having her coffee served by a “Moor”. Representatives of the African diaspora were not uncommon in European princely courts. They belonged, in their function as valets, to the aesthetics of the Wunderkammer, or more precisely to the idea that all the world is present at court. The necklace in the caffettiera comes from Guinea, the traditional name for the West African coast region along the Gulf of Guinea. The trade beads are made of bauxite, which is the world’s main source of aluminium and now one of the most sought-after raw materials in the region. Guinea has the globe’s largest bauxite deposits but remains one of the poorest areas in the world.

Johann Joachim Kändler, Indian Lovers, porcelain, Meissen, mid-18th century. Collection Johann Jacobs Museum.

Caffettiera, Alfonso Bialetti, Italy, after 1945. Collection Johann Jacobs Museum.

Johann Joachim Kändler, Indian Lovers, porcelain, Meissen, mid-18th century. Collection Johann Jacobs Museum.

Previous

Next