Data Privacy Disclaimer

The Johann Jacobs Museum respects your private sphere

When processing personal data, we attach great importance to protecting your private sphere and ensuring that your data are secure. This data protection policy tells you about the data we process, why we need them, and how you can lodge an objection to the processing of your data.

We collect, process and store personal data (including IP addresses) only as permitted by law or if you have given your consent, for example when registering for an event or a service.

What personal data do we collect?

The personal data we collect are limited to information regarding our relationship with you. This includes contact information, such as name, telephone number, address or email address, as well as information relating to projects and events or to your use of our website. Information that cannot be linked to your identity (e.g. statistical information, such as the number of users of our online services) is not considered to be personal data.

How do we collect personal data?

In general, we collect personal data in the following cases: when you apply for a grant from our foundation; when you visit our website; when you communicate with us directly; when you register for our newsletter or an event; when you participate in a survey; or when you provide personal data for other purposes. In all cases, we process your data only for a specific purpose, and that purpose is known to you.

Do we pass your data on to third parties?

As a matter of principle, we pass your personal data on to third parties only if we are authorized by law to do so or if you have given your consent. This is the case, for example, when we conduct external project evaluations in agreement with you. Further information on this topic can be found in the relevant grant agreement. When data are transmitted abroad, we comply with the relevant legal provisions (guaranteeing appropriate protection).

External service providers that process data on our behalf are contractually obliged to comply fully with the Federal Act on Data Protection. We make sure that such external service providers are capable of safeguarding data. Our prior consent is required before they are permitted to transfer responsibility for processing personal data to a third party.

How long do we retain your personal data?

We retain your data as long as necessary for our business relationship with you, or as long as we have a legitimate interest in continuing to store the information. We delete your personal data in all other cases, except when continued storage is required under the law (for example, we are legally obligated to retain documents such as contracts and invoices for a period of 10 years).

What data are processed when you use our website?

In general, you may visit our website without providing personal information. When you visit the site, our servers make a temporary record of each access in a log file. The following technical data are collected and stored until they are automatically deleted after no more than seven months:

- The IP address of the computer used to access the site

- The date and time of access

- The website from which access was obtained, as well as the search term used, as applicable

- The name and URL of the accessed file

- The search queries used

- Your computer’s operating system (shown by the user agent)

- The browser you are using (shown by the user agent)

- The type of device, if access is obtained through a mobile telephone

- The transmission protocol used

By collecting and processing these data, we promote system security and stability, allow for error and performance analysis, and serve internal statistical needs. This also enables us to optimize our online services. In addition, IP addresses are used to preset the website language. Finally, we insert cookies and use cookie-based applications and tools when users access our website. More detailed information can be found in the next section.

What are cookies, and when are they used?

Cookies are small text files that are placed on your computer when you visit our website. When you return to the website, your browser transmits the information contained in the cookies back to us, and this allows the system to recognize your terminal device. With the help of cookies, we are able to optimize our website and facilitate its use.

When you visit our website, a popup message informs you of our use of cookies and of the fact that visiting the site implies your consent.

If you opt not to permit the use of cookies, you may deactivate and delete all cookies at any time. For more information, consult your browser’s help function. If you choose to deactivate cookies, however, certain functions on our website may no longer be available to you. The deactivation or deletion process must be repeated if you use a different browser or terminal device.

To manage or deactivate the use of cookies by third-party providers, visit the following website: http://www.youronlinechoices.com/de/ praferenzmanagement. As we do not operate this website, we are not responsible for it, nor do we have any influence on its contents or accessibility.

How do we use tracking tools?

We need statistical information about the use of our online services (in particular our website and newsletter) to make them more user-friendly, measure their range and conduct market research. We use web analytics tools for this purpose, specifically WP Statistics. The user profiles we create using these tools and cookies are not linked to personal data. The tools do not use visitors’ IP addresses, or they abbreviate them immediately after the information is collected.

In addition to the data listed above (see “What data are processed when you use our websites?”), we gather the following information:

- The user’s navigation path on the website

- The length of time the user spends on the website or subpage

- The subpage from which the user leaves the website

- The country, region or city from which the website is accessed

- The terminal device (type, version, color depth, resolution, width and height of the browser window)

- Repeat or new visitor

This information is used to analyze website use. As explained in the previous section, you can avoid the creation of a user profile by deactivating the use of all cookies.

Social media

Our website contains plugins and links to several social networks (Facebook, Instagram). The links are marked with the logos of the providers. Clicking on a link takes you to the relevant social media platform, where this data protection policy does not apply. The provisions that apply there can be found in the data protection policy posted on the respective provider’s website.

Personal information is not transmitted to the social media provider until you click on a link or plugin. By accessing the linked site, you are allowing the provider to process your data. We have no influence over such data processing, nor do we have information about the extent of data collection, the purposes for which the data are processed, or the retention period. We have no information about the deletion of data by the plugin provider.

Newsletter

You can subscribe to newsletters through our online services. We use the so-called “double opt-in” method; this means that if you want to receive our email newsletter, you must confirm your request by clicking on a link in a message. If you subsequently decide that you no longer want to receive our newsletter, you can cancel your subscription at any time, effective going forward, by revoking your consent. This can be done by clicking on a link in the email newsletter. Alternatively, you can contact us using the information in the Contact section.

What rights do you have concerning your personal data?

You have the following rights:

- You are entitled to request information about your stored data.

- You may request that your personal data be corrected, supplemented, blocked or deleted.

- If you have consented to the processing of your data, you may revoke that consent at any time, effective going forward.

You may do so via letter or email. See Contact section.

Data security

We use appropriate technical and organizational security measures to protect stored personal data against manipulation, partial or total loss, and unauthorized access by third parties. Our security measures are continually upgraded as technology advances.

Amending this data protection policy

We reserve the right to amend or supplement this policy at any time, as we see fit and in accordance with data protection law. Please consult this policy on a regular basis.

Contact

If you have questions about your rights concerning your personal data or related issues, please contact:

Jacobs Foundation

Head of Operations

Seefeldquai 17

Post Office Box

8034 Zurich

Switzerland

jf@jacobsfoundation.org

Tel. +41 (0)44 388 61 23

The Niger Delta has long been linked up to the global economy.From the 16th century onwards, the African west coast was amain centre of the transatlantic slave trade. Since the discovery of crude oil in the 1950s, a trade every bit as lucrative as it is dirty has developed in the Delta: multinational concerns pump the “black gold” out of the earth and transport it through pipelines hundreds of kilometres long to the ocean, where tankers wait under naval protection.

The Niger Delta has long been linked up to the global economy.From the 16th century onwards, the African west coast was amain centre of the transatlantic slave trade. Since the discovery of crude oil in the 1950s, a trade every bit as lucrative as it is dirty has developed in the Delta: multinational concerns pump the “black gold” out of the earth and transport it through pipelines hundreds of kilometres long to the ocean, where tankers wait under naval protection.

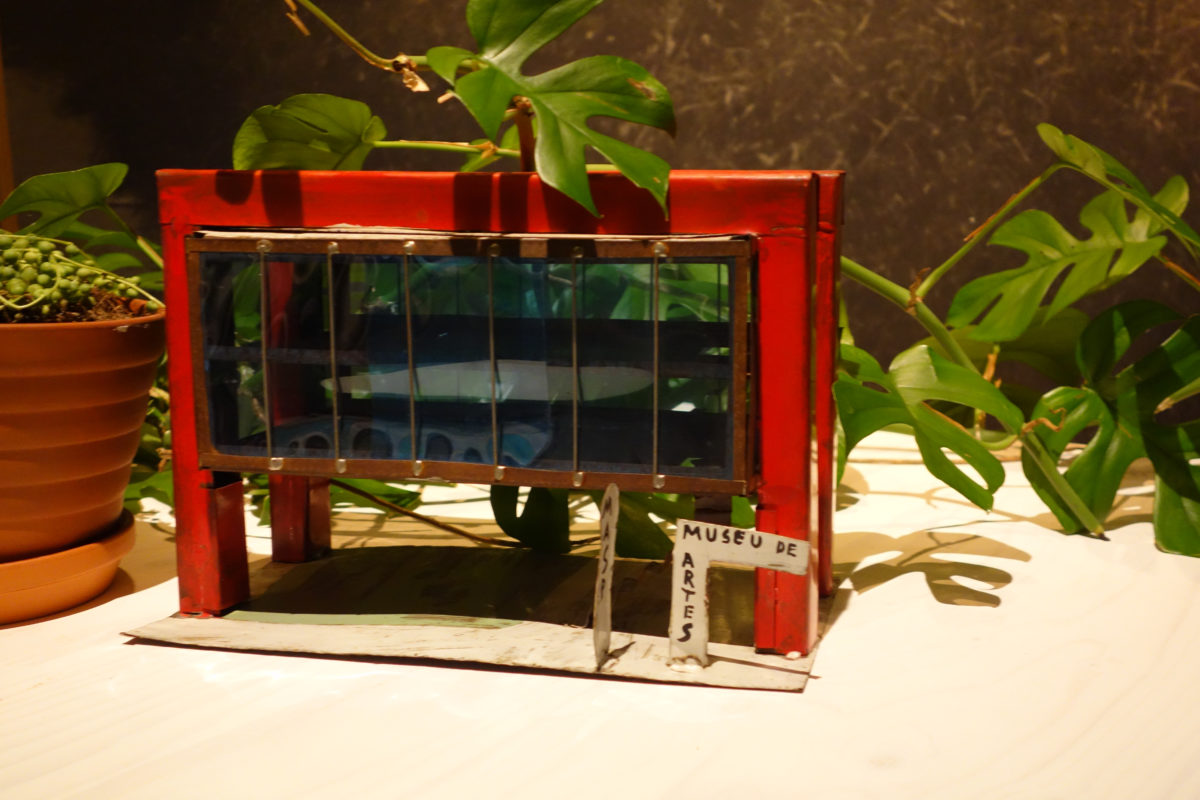

Bo Bardi’s somewhat analytical choice of presentation, which directs the gaze of museum visitors to every single item while underscoring both formal and structural relationships, was an acknowledgement both of the creative drive of the simple population and of the crude materials of which the items were made. Bo Bardi’s collection, however, was not restricted merely to displaying objects that provided an image of society: it understood society as a dynamic and changing phenomenon. This becomes clear when we look at the gigantic open staircase that Bo Bardi installed in the Museum.

Bo Bardi’s somewhat analytical choice of presentation, which directs the gaze of museum visitors to every single item while underscoring both formal and structural relationships, was an acknowledgement both of the creative drive of the simple population and of the crude materials of which the items were made. Bo Bardi’s collection, however, was not restricted merely to displaying objects that provided an image of society: it understood society as a dynamic and changing phenomenon. This becomes clear when we look at the gigantic open staircase that Bo Bardi installed in the Museum. Guilherme Gaensly (1843-1928) took the group photograph in front of the Hospedaria de Imigrantes (immigration centre) in São Paulo in the early 20th century. Once equipped with a passport and a job, immigrants from Europe would set out from here to start their new lives. The barefooted girl to the left of the foreground grips her clothing tightly, as if it gave her something solid to hold onto, and expresses the general mood: a mixture of abashed curiosity and scepticism. The fatigue of several weeks at sea is apparent, as well as the sense of relief at having finally arrived. New arrivals sent group photographs like these as postcards to their family and relations in the old world.

Guilherme Gaensly (1843-1928) took the group photograph in front of the Hospedaria de Imigrantes (immigration centre) in São Paulo in the early 20th century. Once equipped with a passport and a job, immigrants from Europe would set out from here to start their new lives. The barefooted girl to the left of the foreground grips her clothing tightly, as if it gave her something solid to hold onto, and expresses the general mood: a mixture of abashed curiosity and scepticism. The fatigue of several weeks at sea is apparent, as well as the sense of relief at having finally arrived. New arrivals sent group photographs like these as postcards to their family and relations in the old world.

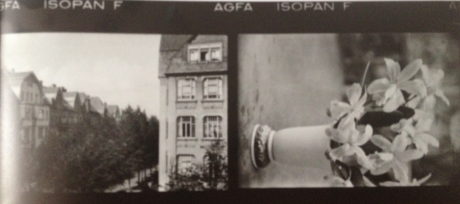

Meissen porcelain was produced from 1710 onwards on the Albrechtsburg in Meissen an der Elbe for August the Strong (1670-1733), later known as Friedrich August I, Elector of Saxony, and from 1697 as August II, King of Poland. It came as a response to the monopoly on “white gold” held for centuries mainly by China, but also by Japan. The history of European porcelain began with its invention by alchemist and pharmacist Johann Friedrich Böttger, who had developed its precursor in the form of a hard red stoneware, known as Böttgersteinzeug, at the Saxon court in 1706. A coffee pot complete with cup and saucer by Böttger are part of the frieze at the Johann Jacobs Museum (in the hallway on the ground floor).

Meissen porcelain was produced from 1710 onwards on the Albrechtsburg in Meissen an der Elbe for August the Strong (1670-1733), later known as Friedrich August I, Elector of Saxony, and from 1697 as August II, King of Poland. It came as a response to the monopoly on “white gold” held for centuries mainly by China, but also by Japan. The history of European porcelain began with its invention by alchemist and pharmacist Johann Friedrich Böttger, who had developed its precursor in the form of a hard red stoneware, known as Böttgersteinzeug, at the Saxon court in 1706. A coffee pot complete with cup and saucer by Böttger are part of the frieze at the Johann Jacobs Museum (in the hallway on the ground floor).

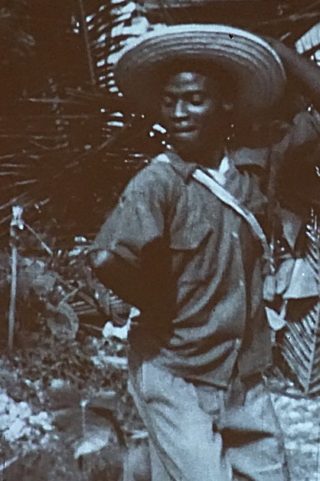

Filmmaker and anthropologist Maya Deren went to Haiti for the first time in 1947 with a view to studying local dance forms. Once there, she realized that these dance forms were inseparably bound up with the religious rites and rituals of vodou. If she were to acquire a deeper understanding of vodou in all its spiritual and emotional dimensions, she would have become part of the ritual community herself. Vodou is a syncretic religion. It combines the various African religions of the slaves shipped to Haiti from 1502 onwards, the Catholicism of the Spanish and French colonial masters, and Indian beliefs brought to Haiti by Caribbean tribes who had been forced into slavery by the Spaniards.

Filmmaker and anthropologist Maya Deren went to Haiti for the first time in 1947 with a view to studying local dance forms. Once there, she realized that these dance forms were inseparably bound up with the religious rites and rituals of vodou. If she were to acquire a deeper understanding of vodou in all its spiritual and emotional dimensions, she would have become part of the ritual community herself. Vodou is a syncretic religion. It combines the various African religions of the slaves shipped to Haiti from 1502 onwards, the Catholicism of the Spanish and French colonial masters, and Indian beliefs brought to Haiti by Caribbean tribes who had been forced into slavery by the Spaniards. The Haitian slave rebellion (1791-1804), which ended successfully with the defeat of Napoleon’s army in 1802 and the establishment of the first “black” republic, had been strongly inspired by the French Revolution, whose lessons were carried from Paris to Haiti by educated mulattoes. The slave uprising was triggered by a vodou religious ceremony, during which a priestess was “possessed” by a spirit – a Loa – who serves the creator deity Bon Dieu. This sprit was Erzulie Dantor, the Loa of women and children and a militant figure whose symbols included the sword and a pierced heart. The vodou banner, which is clearly in the style of depictions of Madonna, was produced in the mid-20th century at the time when Maya Deren was in Haiti. Apart from the symbols of Erzulie Dantor – a sword and dagger – the female figure also bears features – a heart – of the other central female sprit, Erzulie Freda. Unlike the belligerent Erzulie Dantor, Freda stands for love, dreams and luxury. On the lower edge of the banner we find the ritual drums that were used during religious ceremonies to summon up spirits and incite them to take possession of human beings.

The Haitian slave rebellion (1791-1804), which ended successfully with the defeat of Napoleon’s army in 1802 and the establishment of the first “black” republic, had been strongly inspired by the French Revolution, whose lessons were carried from Paris to Haiti by educated mulattoes. The slave uprising was triggered by a vodou religious ceremony, during which a priestess was “possessed” by a spirit – a Loa – who serves the creator deity Bon Dieu. This sprit was Erzulie Dantor, the Loa of women and children and a militant figure whose symbols included the sword and a pierced heart. The vodou banner, which is clearly in the style of depictions of Madonna, was produced in the mid-20th century at the time when Maya Deren was in Haiti. Apart from the symbols of Erzulie Dantor – a sword and dagger – the female figure also bears features – a heart – of the other central female sprit, Erzulie Freda. Unlike the belligerent Erzulie Dantor, Freda stands for love, dreams and luxury. On the lower edge of the banner we find the ritual drums that were used during religious ceremonies to summon up spirits and incite them to take possession of human beings.